30 April 2018

Museum Monday 2018/18

as a follow-up to last week's picture for Shakespeare's birthday, here is one of the bas-reliefs outside the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC, illustrating famous scenes from the plays: this one obviously is Titania and a surprisingly hunky Bottom the Weaver from A Midsummer Night's Dream

27 April 2018

26 April 2018

fun stuff I may or may not get to: May 2018

Theatrical

Exit Theatre presents Congresswomen, freely adapted from the Ecclesiazusae of Aristophanes as well as directed by Stuart Bousel, from 3 to 26 May.

Cal Performances presents Ex Machina, director Robert Lepage's production group, in 887, a one-man show about his childhood; that's 4 and 5 (matinee) May in Zellerbach Hall.

Cal Performances presents the Japanese taiko troupe TAO in Drum Heart on 6 May in Zellerbach Hall.

San Francisco Playhouse presents An Entomologist's Love Story, written by Melissa Ross and directed by Giovanna Sardelli, from 8 May to 23 June.

Shotgun Players presents Dry Land, written by Ruby Rae Spiegel and directed by Ariel Craft, about two girls on a high school swim team, from 17 May to 17 June.

Operatic

The San Francisco Conservatory of Music presents a double-bill of John Musto's Bastianello and William Bolcom's Lucrezia (in the world premiere of a new orchestration by Bolcom, commissioned by the Conservatory), directed by Heather Mathews and conducted by Curt Pajer, on 4 and 6 (matinee) May; free but reservations are required.

Orchestral

It's Guest Conductor Month at the San Francisco Symphony: Juraj Valčuha conducts Andrew Norman's Unstuck, the Brahms Violin Concerto with soloist Ray Chen, and the Prokofiev 3 on 3 - 5 May; Stéphane Denève conducts Ibert's Escales, the Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto 1 with soloist Gautier Capuçon, Guillaume Connesson's E chiaro nella valle il fiume appare, and Respighi's Pines of Rome on 10 - 12 May; Itzhak Perlman conducts and plays violin in a Bach concerto for violin, oboe, and orchestra (Eugene Izotov on solo oboe), the Tchaikovsky Serenade for Strings, and Elgar's Enigma Variations on 17 and 19 - 20 May; David Robertson leads the band in Brett Dean's Engelsflügel, the Haydn 102, and the Brahms Piano Concerto 1 with soloist Kirill Gerstein on 25 - 26 May; and Semyon Bychkov leads us into June with Taneyev's Oresteia Overture, the Bruch Concerto for Two Pianos with soloists Katia and Marielle Labèque, and the Tchaikovsky 2, the Little Russian, and that's on 31 May and 1 - 2 June.

On 13 May the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra, led by Christian Reif, plays Ligeti's Concert Românesc, the suite from Fauré's Pelléas et Mélisande, and Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, a program that looks much more interesting than lots of the programs on the "adult" stage.

Michael Morgan leads the Oakland Symphony in Leonard Bernstein's Serenade after Plato's Symposium for Violin and Orchestra (with soloist Liana Bérubé) and the Tchaikovsky 6, the Pathétique, on 18 May at the Paramount Theater.

New Century Chamber Orchestra closes its season with Guest Concertmaster Zachary DePue leading the west coast premiere of a new piano concerto by Philip Glass, with soloist Simone Dinnerstein. The program also features works by Bach, Purcell, Dessner, and Geminiani, and you can hear it 16 May at the Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts, 17 May at First Congregational in Berkeley, 18 May at the Oshman Family Jewish Community Center in Palo Alto, 19 May at Herbst Theater in San Francisco, and 20 May (matinee) at the Osher Marin Jewish Community Center in San Rafael.

Chamber Music

A small ensemble of San Francisco Symphony musicians will perform chamber works by Fauré, Harbison, Rouse, and Dvořák in unfortunately cavernous Davies Hall on 6 May; then on 13 May, this time up at the Gunn Theater at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco Symphony players Alexander Barantschik (violin), Jonathan Vinocour (viola), and Peter Wyrick (cello) will play Shostakovich and Brahms.

On 19 May Old First Concerts presents the Friction Quartet, joined by theremin player Thorwald Jørgensen, in Dalit Warshaw's Transformations and the US premiere of Simon Bertrand's The Invisible Singer.

Early / Baroque Music

Pocket Opera presents Handel's Semele, with Maya Kherani in the title role, on 29 April at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco and 6 May at the Hillside Club in Berkeley (both performances are matinees).

San Francisco Performances presents Jordi Savall on viola da gamba, his ensemble Hespèrion XXI, and Carlos Núñez on Galacian bagpipes in an exploration of early Celtic music; that's 3 May at Herbst Theater.

The San Francisco Early Music Society presents a program of baroque rarities featuring soprano Hana Blažíková and cornettist Bruce Dickey. They will be joined by Ingrid Matthews and Tekla Cunningham on violin, Joanna Blendulf on viol, Michael Sponseller on organ and harpsichord, and Stephen Stubbs on theorbo and guitar in works by Biagio Marini, Nicolò Corradini, Giovanni Battista Bassani, Giacomo Carissimi, Tarquinio Merula, Alessandro Scarlatti, and Maurizio Cazzati. That's 4 May at St Mark's Lutheran in San Francisco, 5 May at St Mary Magdalen in Berkeley, and 6 May at Bing Concert Hall at Stanford University.

American Bach Soloists presents two concerts this month: baritone William Sharp sings Bach in the Chapel of Grace in Grace Cathedral in San Francisco on 4 May, and Jeffrey Thomas leads the ensemble in Bach's Orchestral Suites on 11 May in St Stephen's in Belvedere, on 12 May at First Congregational in Berkeley, on 13 May at St Mark's Lutheran in San Francisco, and on 14 May at Davis Community Church in Davis.

On 13 May Ragnar Bohlin leads the San Francisco Symphony Chorus in works by Bach, including the Magnificat, and Arvo Pärt.

Paul Flight leads Chora Nova in works by Johann Adolph Hasse and Jan Dismas Zelenka at First Congregational in Berkeley on 26 May.

Modern / Contemporary Music

Volti ends its season with Bay and Beyond, a program featuring composers with strong ties to the Bay Area: Danny Clay, Žibuoklė Martinaitytė, Robin Estrada, Terry Riley, and Henry Cowell. You can hear them on 4 May at the Noe Valley Ministry in San Francisco or 6 May at the Berkeley Art Museum / Pacific Film Archive.

The Left Coast Chamber Ensemble closes out its season with a rare performance of Schoenberg's Serenade for Baritone and Seven Players, along with Sándor Jemnitz's Trio for Violin, Viola, and Guitar and the world premiere of Rinconcito by Nicolas Lell Benavides. That's 19 May at the Berkeley Hillside Club and 21 May at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

As always, check the entire schedule for the Center for New Music, as events are frequently added after I've posted the monthly preview. Some things that jump out at me from the current listings for May are: soprano Jane Spencer Mills, pianist Ian Scarfe, and flutist Jessie Nucho in Of Cats, the Moon, and Rain on 2 May; Solo Collective, featuring UC-Berkeley composers in Myra Melford's composition seminar on 3 May; the Brooklyn Art Song Society on 12 May; the Ghost Ensemble on 17 May; Kurt Rohde's Farewell Tour – Part One on 18 May; Friction Quartet concerts on 20 May (music from composers of the John Adams Young Composers Program) and 25 May (works by Pascal Le Boeuf and Danny Clay); and Diana Wade's You Made it Weird, San Francisco on 31 May.

See also the Philip Glass premiere at New Century Chamber Orchestra under Orchestral and the Volti concert under Choral.

Keyboards & Strings

Cal Performances presents pianist Leif Ove Andsnes playing Nielsen, Sibelius, Beethoven, Schubert, and Jörg Widmann at First Congregational on 4 May.

San Francisco Performances and the San Francisco Symphony present pianist Yuja Wang at Davies Hall on 6 May, playing Chopin, Scriabin, Ligeti, and Prokofiev. [UPDATE: Unfortunately Yuja Wang has had to cancel this concert due to illness. I hope she recovers soon!]

On 6 May Old First Concerts commemorates the centennial of the end of the First World War with a concert featuring the Ives Collective, tenor Brian Thorsett, and violinist Jessica Chang in music written during the war or by artists involved in the war.

Chamber Music San Francisco presents two San Francisco debut piano recitals at Herbst Theater this month: on 5 May Yeol Eum Son plays Mozart, Pärt, Ravel, Schubert (as adapted by Liszt), Rachmaninoff, and Gulda; and on 20 May Alexander Gavrylyuk plays Bach (as adapted by Busoni), Haydn, Chopin, Scriabin, and Rachmaninoff. (Gavrylyuk will repeat his program on 19 May in Walnut Creek and on 21 May in Palo Alto.)

On 18 May Old First Concerts presents the second concert of its four-concert series marking the death-centennial of Debussy; this one features pianists Daniel Glover, Laura Magnani, Keisuke Nakagoshi, Robert Schwartz, and Brent Smith along with soprano Christa Pfeiffer and mezzo-soprano Katherine McKee in Pour le piano, Images Books 1 & II, Estampes, Suite bergamasque, Salut printemps, and other works.

Old First Concerts presents pianist Stephen Porter on 20 May in a program of religious music by Franz Liszt.

Felix Hell gives an organ recital at Davies Hall, presented by the San Francisco Symphony, on 27 May (matinee).

Pianist Sarah Cahill will perform works by Lou Harrison, Jon Scoville, Paul Dresher, and Ruth Crawford at the Berkeley Art Museum on 27 May (matinee). The performance is free with admission to the galleries, and there are several interesting exhibits there now.

Vocalists

The great Audra McDonald is spending the evening of 18 May with the San Francisco Symphony, led by Andy Einhorn; the program has not been announced (other than "Broadway classics and contemporary musical theater works") but all you really need to know is that it's Audra McDonald.

Talking

Cal Performances presents an evening with David Sedaris at Zellerbach Hall on 8 May.

Visual Arts

René Magritte: The Fifth Season, an in-depth look at the surrealist painter's late career, opens on 19 May at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and runs until 28 October.

Cinematic

Cal Performances presents the eco ensemble performing a new score by Martin Matalon for The Oyster Princess, Ernst Lubitsch's 1919 comedy (it's not as slyly subtle as his later films, but it's still Lubitsch) at Zellerbach Playhouse on 6 May. Departing Cal Performances Director Matías Tarnopolsky will interview Matalon on stage before the film.

The Golden Gate Symphony, led by Urs Leonhardt Steiner, will perform Prokofiev's score at a screening of Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky (with mezzo-soprano Elizabeth Baker as soloist) at the Southern Pacific Brewing Company on 21 May.

On 30 May the Berkeley Art Museum / Pacific Film Archive presents a program of Garbo rarities from the Swedish Film Institute, including the bit remaining from Victor Seastrom's The Divine Woman, which I think is the only Garbo film that doesn't survive intact. Archivist Jon Wengström, in town to receive an award from the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, will discuss the clips and put them in perspective and Stephen Horne will accompany on piano.

And we close out the month with the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, which is always a highlight of the year. The 2018 edition of the annual festival runs from 30 May to 3 June at the period-appropriate Castro Theater, with twenty-three programs (with live musical accompaniment) highlighting the diversity and artistry of silent film, ranging from familiar classics like Buster Keaton's Battling Butler to newly discovered and restored rarities like E A Dupont's Das Alte Gesetz (The Ancient Law) or Richard Oswald's Der Hund von Baskerville (The Hound of the Baskervilles). I have my festival pass and will be sitting in the dark for four days, living on popcorn and dreams.

Exit Theatre presents Congresswomen, freely adapted from the Ecclesiazusae of Aristophanes as well as directed by Stuart Bousel, from 3 to 26 May.

Cal Performances presents Ex Machina, director Robert Lepage's production group, in 887, a one-man show about his childhood; that's 4 and 5 (matinee) May in Zellerbach Hall.

Cal Performances presents the Japanese taiko troupe TAO in Drum Heart on 6 May in Zellerbach Hall.

San Francisco Playhouse presents An Entomologist's Love Story, written by Melissa Ross and directed by Giovanna Sardelli, from 8 May to 23 June.

Shotgun Players presents Dry Land, written by Ruby Rae Spiegel and directed by Ariel Craft, about two girls on a high school swim team, from 17 May to 17 June.

Operatic

The San Francisco Conservatory of Music presents a double-bill of John Musto's Bastianello and William Bolcom's Lucrezia (in the world premiere of a new orchestration by Bolcom, commissioned by the Conservatory), directed by Heather Mathews and conducted by Curt Pajer, on 4 and 6 (matinee) May; free but reservations are required.

Orchestral

It's Guest Conductor Month at the San Francisco Symphony: Juraj Valčuha conducts Andrew Norman's Unstuck, the Brahms Violin Concerto with soloist Ray Chen, and the Prokofiev 3 on 3 - 5 May; Stéphane Denève conducts Ibert's Escales, the Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto 1 with soloist Gautier Capuçon, Guillaume Connesson's E chiaro nella valle il fiume appare, and Respighi's Pines of Rome on 10 - 12 May; Itzhak Perlman conducts and plays violin in a Bach concerto for violin, oboe, and orchestra (Eugene Izotov on solo oboe), the Tchaikovsky Serenade for Strings, and Elgar's Enigma Variations on 17 and 19 - 20 May; David Robertson leads the band in Brett Dean's Engelsflügel, the Haydn 102, and the Brahms Piano Concerto 1 with soloist Kirill Gerstein on 25 - 26 May; and Semyon Bychkov leads us into June with Taneyev's Oresteia Overture, the Bruch Concerto for Two Pianos with soloists Katia and Marielle Labèque, and the Tchaikovsky 2, the Little Russian, and that's on 31 May and 1 - 2 June.

On 13 May the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra, led by Christian Reif, plays Ligeti's Concert Românesc, the suite from Fauré's Pelléas et Mélisande, and Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, a program that looks much more interesting than lots of the programs on the "adult" stage.

Michael Morgan leads the Oakland Symphony in Leonard Bernstein's Serenade after Plato's Symposium for Violin and Orchestra (with soloist Liana Bérubé) and the Tchaikovsky 6, the Pathétique, on 18 May at the Paramount Theater.

New Century Chamber Orchestra closes its season with Guest Concertmaster Zachary DePue leading the west coast premiere of a new piano concerto by Philip Glass, with soloist Simone Dinnerstein. The program also features works by Bach, Purcell, Dessner, and Geminiani, and you can hear it 16 May at the Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts, 17 May at First Congregational in Berkeley, 18 May at the Oshman Family Jewish Community Center in Palo Alto, 19 May at Herbst Theater in San Francisco, and 20 May (matinee) at the Osher Marin Jewish Community Center in San Rafael.

Chamber Music

A small ensemble of San Francisco Symphony musicians will perform chamber works by Fauré, Harbison, Rouse, and Dvořák in unfortunately cavernous Davies Hall on 6 May; then on 13 May, this time up at the Gunn Theater at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco Symphony players Alexander Barantschik (violin), Jonathan Vinocour (viola), and Peter Wyrick (cello) will play Shostakovich and Brahms.

On 19 May Old First Concerts presents the Friction Quartet, joined by theremin player Thorwald Jørgensen, in Dalit Warshaw's Transformations and the US premiere of Simon Bertrand's The Invisible Singer.

Early / Baroque Music

Pocket Opera presents Handel's Semele, with Maya Kherani in the title role, on 29 April at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco and 6 May at the Hillside Club in Berkeley (both performances are matinees).

San Francisco Performances presents Jordi Savall on viola da gamba, his ensemble Hespèrion XXI, and Carlos Núñez on Galacian bagpipes in an exploration of early Celtic music; that's 3 May at Herbst Theater.

The San Francisco Early Music Society presents a program of baroque rarities featuring soprano Hana Blažíková and cornettist Bruce Dickey. They will be joined by Ingrid Matthews and Tekla Cunningham on violin, Joanna Blendulf on viol, Michael Sponseller on organ and harpsichord, and Stephen Stubbs on theorbo and guitar in works by Biagio Marini, Nicolò Corradini, Giovanni Battista Bassani, Giacomo Carissimi, Tarquinio Merula, Alessandro Scarlatti, and Maurizio Cazzati. That's 4 May at St Mark's Lutheran in San Francisco, 5 May at St Mary Magdalen in Berkeley, and 6 May at Bing Concert Hall at Stanford University.

American Bach Soloists presents two concerts this month: baritone William Sharp sings Bach in the Chapel of Grace in Grace Cathedral in San Francisco on 4 May, and Jeffrey Thomas leads the ensemble in Bach's Orchestral Suites on 11 May in St Stephen's in Belvedere, on 12 May at First Congregational in Berkeley, on 13 May at St Mark's Lutheran in San Francisco, and on 14 May at Davis Community Church in Davis.

On 13 May Ragnar Bohlin leads the San Francisco Symphony Chorus in works by Bach, including the Magnificat, and Arvo Pärt.

Paul Flight leads Chora Nova in works by Johann Adolph Hasse and Jan Dismas Zelenka at First Congregational in Berkeley on 26 May.

Modern / Contemporary Music

Volti ends its season with Bay and Beyond, a program featuring composers with strong ties to the Bay Area: Danny Clay, Žibuoklė Martinaitytė, Robin Estrada, Terry Riley, and Henry Cowell. You can hear them on 4 May at the Noe Valley Ministry in San Francisco or 6 May at the Berkeley Art Museum / Pacific Film Archive.

The Left Coast Chamber Ensemble closes out its season with a rare performance of Schoenberg's Serenade for Baritone and Seven Players, along with Sándor Jemnitz's Trio for Violin, Viola, and Guitar and the world premiere of Rinconcito by Nicolas Lell Benavides. That's 19 May at the Berkeley Hillside Club and 21 May at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

As always, check the entire schedule for the Center for New Music, as events are frequently added after I've posted the monthly preview. Some things that jump out at me from the current listings for May are: soprano Jane Spencer Mills, pianist Ian Scarfe, and flutist Jessie Nucho in Of Cats, the Moon, and Rain on 2 May; Solo Collective, featuring UC-Berkeley composers in Myra Melford's composition seminar on 3 May; the Brooklyn Art Song Society on 12 May; the Ghost Ensemble on 17 May; Kurt Rohde's Farewell Tour – Part One on 18 May; Friction Quartet concerts on 20 May (music from composers of the John Adams Young Composers Program) and 25 May (works by Pascal Le Boeuf and Danny Clay); and Diana Wade's You Made it Weird, San Francisco on 31 May.

See also the Philip Glass premiere at New Century Chamber Orchestra under Orchestral and the Volti concert under Choral.

Keyboards & Strings

Cal Performances presents pianist Leif Ove Andsnes playing Nielsen, Sibelius, Beethoven, Schubert, and Jörg Widmann at First Congregational on 4 May.

San Francisco Performances and the San Francisco Symphony present pianist Yuja Wang at Davies Hall on 6 May, playing Chopin, Scriabin, Ligeti, and Prokofiev. [UPDATE: Unfortunately Yuja Wang has had to cancel this concert due to illness. I hope she recovers soon!]

On 6 May Old First Concerts commemorates the centennial of the end of the First World War with a concert featuring the Ives Collective, tenor Brian Thorsett, and violinist Jessica Chang in music written during the war or by artists involved in the war.

Chamber Music San Francisco presents two San Francisco debut piano recitals at Herbst Theater this month: on 5 May Yeol Eum Son plays Mozart, Pärt, Ravel, Schubert (as adapted by Liszt), Rachmaninoff, and Gulda; and on 20 May Alexander Gavrylyuk plays Bach (as adapted by Busoni), Haydn, Chopin, Scriabin, and Rachmaninoff. (Gavrylyuk will repeat his program on 19 May in Walnut Creek and on 21 May in Palo Alto.)

On 18 May Old First Concerts presents the second concert of its four-concert series marking the death-centennial of Debussy; this one features pianists Daniel Glover, Laura Magnani, Keisuke Nakagoshi, Robert Schwartz, and Brent Smith along with soprano Christa Pfeiffer and mezzo-soprano Katherine McKee in Pour le piano, Images Books 1 & II, Estampes, Suite bergamasque, Salut printemps, and other works.

Old First Concerts presents pianist Stephen Porter on 20 May in a program of religious music by Franz Liszt.

Felix Hell gives an organ recital at Davies Hall, presented by the San Francisco Symphony, on 27 May (matinee).

Pianist Sarah Cahill will perform works by Lou Harrison, Jon Scoville, Paul Dresher, and Ruth Crawford at the Berkeley Art Museum on 27 May (matinee). The performance is free with admission to the galleries, and there are several interesting exhibits there now.

Vocalists

The great Audra McDonald is spending the evening of 18 May with the San Francisco Symphony, led by Andy Einhorn; the program has not been announced (other than "Broadway classics and contemporary musical theater works") but all you really need to know is that it's Audra McDonald.

Talking

Cal Performances presents an evening with David Sedaris at Zellerbach Hall on 8 May.

Visual Arts

René Magritte: The Fifth Season, an in-depth look at the surrealist painter's late career, opens on 19 May at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and runs until 28 October.

Cinematic

Cal Performances presents the eco ensemble performing a new score by Martin Matalon for The Oyster Princess, Ernst Lubitsch's 1919 comedy (it's not as slyly subtle as his later films, but it's still Lubitsch) at Zellerbach Playhouse on 6 May. Departing Cal Performances Director Matías Tarnopolsky will interview Matalon on stage before the film.

The Golden Gate Symphony, led by Urs Leonhardt Steiner, will perform Prokofiev's score at a screening of Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky (with mezzo-soprano Elizabeth Baker as soloist) at the Southern Pacific Brewing Company on 21 May.

On 30 May the Berkeley Art Museum / Pacific Film Archive presents a program of Garbo rarities from the Swedish Film Institute, including the bit remaining from Victor Seastrom's The Divine Woman, which I think is the only Garbo film that doesn't survive intact. Archivist Jon Wengström, in town to receive an award from the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, will discuss the clips and put them in perspective and Stephen Horne will accompany on piano.

And we close out the month with the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, which is always a highlight of the year. The 2018 edition of the annual festival runs from 30 May to 3 June at the period-appropriate Castro Theater, with twenty-three programs (with live musical accompaniment) highlighting the diversity and artistry of silent film, ranging from familiar classics like Buster Keaton's Battling Butler to newly discovered and restored rarities like E A Dupont's Das Alte Gesetz (The Ancient Law) or Richard Oswald's Der Hund von Baskerville (The Hound of the Baskervilles). I have my festival pass and will be sitting in the dark for four days, living on popcorn and dreams.

23 April 2018

Museum Monday 2018/17

April 23 is the traditional date of Shakespeare's birth (1564), and the recorded date of his death (1616), so in honor of the greatest poet in the English language, here is a copy of the First Folio from the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC.

April 23 is also the feast of St George, so here's a bonus: the saint as portrayed by the painter nicknamed Il Sodoma, from the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC:

And here's a view of the poor vanquished dragon in the same painting, and he surely deserves a feast day of his own:

April 23 is also the feast of St George, so here's a bonus: the saint as portrayed by the painter nicknamed Il Sodoma, from the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC:

And here's a view of the poor vanquished dragon in the same painting, and he surely deserves a feast day of his own:

20 April 2018

16 April 2018

Michael Hersch, American Visionary at the NOVA Chamber Music Series

I don't remember when or

why I started listening to Michael Hersch's music, but I've been doing so for years, and in all that time I had only heard one piece live – a song he wrote

for Thomas Hampson, based on a passage from Thomas Hardy. So when I was randomly checking the composer's

website and saw that in the last week of January 2018 the NOVA Chamber Music Series in Salt Lake City

was performing three substantial works by him – The Vanishing

Pavilions, Last Autumn, and On the Threshold of Winter –

I decided it would be a good idea to take my first trip to the Beehive State.

I flew in on Sunday

afternoon, which gave me enough time to figure out the location of the concert

venue (the Libby Gardner Concert Hall in Presidents Circle at the University of

Utah) in relation to my hotel (the University Park Marriott), before the first

concert: The Vanishing Pavilions, played by pianist and NOVA

Artistic Director Jason Hardink. I had checked for hotels near the University

of Utah and found a nice one about a mile away, though since the music building

is on the other side of the campus it was actually two miles away. That proved

to be a good distance to walk after the concerts, and I was lucky the weather

was not as wet and cold as it might have been, so I could ponder and decompress

under the stars.

Each concert was preceded by a short conversation between Hersch and Hardink in a small lecture room down the hall from the

auditorium. (I was very impressed that Hardink could

conduct an interview right before playing a massive two-and-a-half-hour solo

piano piece, but he's clearly a man of many talents). I took some brief notes

on what Hersch said; one thing I wrote out right away was his response when he

was asked what the impetus was for his composition: he responded that years ago

he had started writing only pieces that compelled him because he is "not

talented enough to write pieces that don't feel necessary." That really

struck me, as our culture tends to favor the divine afflatus over the

conscientious craftsman, but I think I saw what he meant: there's tremendous skill and

also sensitivity in producing music by the yard, so to speak, the way a

composer for film would, as opposed to being guided by your own inner

necessity. It seemed typical of a certain tendency towards self-effacement on

Hersch's part. He is soft-spoken, considerate with his words, and not at all

anecdotal. He would answer each question and then fall silent.

I had sort of assumed

that American Visionary was the name NOVA chose for the

festival just because visionary always sounds good, but as I

listened to Hersch talk about his approach to composition I began to understand that the word had been chosen more precisely than I had assumed. I had not

previously considered Hersch a Wagner-like composer, but like Wagner he writes

pieces of epic length, in a sound world of his own, uncertain if they will ever

actually be performed. He has a distinct way of viewing the world, which I

think often gets misunderstood. After Hampson sang that song, he courteously

gestured to Hersch, who turned out to be in the audience, and made a deprecating little remark

about how bleak his world view was. To me it came across as a bit dismissive, even

condescending. I think Hersch sees the world clearly and tried to express his

view – his vision – clearly. Obviously it's one I'm sympathetic with, and I've also

been dismissed so often as overly gloomy or grim or pretentious that I bristle with a

sense of personal identification when I heard remarks like the one Hampson made about

Hersch. It was wonderful to be in an audience that was clearly open to what he

was saying and how he was saying it.

Maybe this is a good

point to mention that the people I spoke to at NOVA, particularly Executive

Director Kristin Rector and Digital Content Producer Chris Martin, could not

have been nicer or more welcoming to this visitor from California. And I might as well mention here as well

that my series pass was so inexpensive ($50 for three concerts) that at first I

assumed there was an error on the website. These concerts are clearly going

to count as one of the great bargains as well as one of the most artistically

exciting events of my year.

(the view from my hotel room)

Back to the talk: The

Vanishing Pavilions, like Hersch's ensuing pieces, was written without

regard to its practicality. In fact Hersch, a pianist himself, composed it away

from the instrument so that he would not be guided or bound by his particular

pianistic preferences or defaults. Someone in the audience asked if he would

authorize excerpts to be played, and he said no, though on occasion it has

happened. Hersch mentioned (he brought this up during one of the other talks as

well) that one reason a piece like this isn't done very often is that you need

someone who is not only interested in learning a lengthy piece of new music but

has the technical skills and stamina required to bring it off.

Someone asked about how

he memorized the piece and Hersch replied that there was a process of living

with it for a year after the composition (which I think took more than a year;

I didn't write that bit of information down in my notes). By then he did have a

premiere date for the work and had to scramble a bit as his year of learning

the piece was delayed by the birth of his child. (Hardink also played from

memory, and I think said it took him about a year to learn it.) Hersch was then asked whether composition was an expression of self or of

ideas, and he promptly said it was an expression of the self, which I thought

was interesting in a composer so often seen as intellectual, though he

immediately pointed out that ideas form part of the self, so there really isn't a clear division there.

The Vanishing Pavilions was completed in 2005 and its fifty

segments are divided into two books (there was a brief intermission between the

two halves). It is inspired by lines and images from the works of British poet

Christopher Middleton. Hersch often works from poetry, or rather fragments and

lines of poetry submerged under the music. The program notes by Andrew

Farach-Colton for this piece were reprinted from the CD release. Last Autumn, which is

sort of a companion piece to Pavilions, is similarly in two books

and inspired by lines from W G Sebald. I was intrigued when Hersch mentioned

that he had written a third piece, as yet unperformed, that is five hours long,

inspired by a third poet whom he did not name.

When I found out the

talks were down the hall I expressed some concern about getting the seats I

like (front row) as it was general admission seating, and I was assured that it would not be a problem. Indeed it

was not, as the rest of the audience apparently preferred sitting farther back.

I was in the front, slightly to the left of the pianist, with no one around me for

three rows. It was like a private performance. This is my idea of concert-going

heaven. It seemed almost like a bonus that Hardink's performance was so superb,

with just breath-taking colors. I think, from something I heard him say later,

that the Steinway was his personal instrument, not the one belonging to the concert

hall. The music is turbulent and searching, with lyricism slashed through,

ending abruptly, the vibrations dying into silence. The audience was attentive

and then extremely enthusiastic at the end. Hersch did not come

up to take a bow, letting Hardink have the moment.

The next night it was

back to the Libby Gardner Concert Hall for Last Autumn from

2008, performed by Utah Symphony Acting Principal Horn Edmund Rollett and

cellist Noriko Kishi. In the talk before the performance, Hersch mentioned, if

I understood him correctly, that this was only the third time the piece had

ever been played. He wrote it for specific players; eventually he mentioned

that one of them, the horn player, was his brother (Jamie Hersch). I assume the

cellist on the recording, Daniel Gaisford, is the other

begetter. Apparently the two performers had some sort of falling out that was

linked in some way to the piece (as I said, Hersch is not anecdotal and did not

go into the details). Hersch quipped that he hoped Edmund and Noriko would not

find their friendship damaged by working on the piece. He was asked again about

the length of his pieces: basically, does he know where he's going with them,

or do they just extend as he works on them – his answer was that he knows where

he's going to end up.

The program note for

this piece was by Aaron Grad (it is also available on the recording). The texts

by Sebald were printed in the program. I read them beforehand but decided

not to follow along during the performance, as I can do that easily enough with

the recording and it's such a privilege to hear this music live that I might as

well bask in it. Though a piece for two players doesn't give the impression of

having quite the virtuosic flash of a similarly sized piece for one player,

that impression is misleading. NOVA audiences are lucky to have musicians of

this level of accomplishment playing for them. Again, I had my private concert

experience and was, once again, blown away.

The third and final

concert was on Thursday night, this time at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts

Center in downtown Salt Lake City. Basically the theater was a large empty room, with the audience sitting in three rows of chairs against the long wall opposite the entrance. On the Threshold of Winter, a

monodrama in two acts, had its premiere in 2014. Again, it was written without

a commission and was inspired by poetry, in this case The Bridge by Romanian poet Marin Sorescu, written as he was dying of cancer. (The work was

translated by Adam J Sorkin and Lidia Vinau and the text was adapted, I assume, by Hersch.) The composer was asked in the pre-concert talk about the circumstances

surrounding the creation of this work, which I suspect he would not have

brought up himself. He had a close friend who was diagnosed with ovarian

cancer. What he did not mention in the talk, though it is in the program book,

is that while helping her through her illness he himself was also diagnosed with cancer. He survived, she did not.

One of the difficulties

Hersch mentioned was finding the right singer for the demanding solo role; in

fact he was told that he would never find what he was looking for. It

turned out by chance someone had heard soprano Ah Young Hong singing church

gigs in Baltimore and recommended her and, as Hersch noted, it was the case of

a major artist who had just not yet gotten a break. (She now performs widely

and I believe she is the only singer who has performed On the Threshold

of Winter. She also directed this production.)

Hersch mentioned in the

pre-concert talk that some critics had blamed the piece and him for not

"offering hope" and he responded, with undertones of bewilderment and

exasperation, that he wasn't trying to "offer hope" – he was trying to

express an emotional state. (I was reminded of Hampson's remark about the composer's bleak worldview). The opera is shattering, but you

end up feeling not just shattered but also strengthened – you know, catharsis. That's what seeing someone

create art despite pain can do.

The poems and fragments

of poems that make up the text occasionally mention the hospital or illness-related matters but the general effect is not clinical; it's emotional, psychological, and spiritual. The singer,who is physically fairly small, was wearing a loose somewhat gauzy white gown, suggesting an angel or a ghost as well as a hospital robe. The text is in English but also projected, which is very

helpful because the vocal lines are high and sometimes distorted for expressive effect (as with the operas of Thomas Adès, I wondered about the extent to

which surtitles make this style possible by making the words intelligible). The text formed part of the scenic projections, which were mostly black and white with occasional slashes of red, and mostly of natural scenes. We were more likely to be shown the

bare black branches of trees in winter than the white corridors of a hospital.

The stage is right there in front of us, bare except for some large boxes that Young Hong sometimes sat or walked on or, at one point, knocked over.

I hope there is a recording fairly soon, as this is a score that needs to be listened to several times. (There is, however, a new recording of Ah Young Hong singing Hersch's a breath upwards, along with Babbitt's Philomel.) The music produces

moments of astonishing beauty that collapse into confusion, only to rise again. And here I will praise conductor Tito Muñoz and his band –

Caitlyn Valovick Moore (flute), Luca de la Florin (oboe), Jaren Hinckley

(clarinet), Katie Porter (bass clarinet), Gavin Ryan (percussion), Michael

Sheppard (piano), Hugh Palmer (violin), and Walter Haman (cello) – for their

expert way with the music. Due to the set-up of the theater, I was not isolated

in splendor as I was at the other venue, but the audience was very attentive

and involved and quiet, except for one man in my vicinity who kept clearing his

throat every few minutes. I think it was just a tic that he and his wife had

become unaware of. Not ideal, but it was an interesting counterpoint to a piece

that is to some extent about the breakdown of our physical bodies.

This was the only one of

the three concerts at which Hersch took a bow, mostly because Young Hong

insisted; she also kept directing the enthusiastic applause towards Muñoz and

the band. The whole approach was very collegial, very much that of a community

of people making art together. It was a beautiful feeling to end on, after a

week of intense, emotionally involving music. The whole festival was a triumph.

Bay Area residents who

want to hear Hersch's music live can go to the Ojai North concert at Cal Performances in Berkeley on 15 June, which features his latest work (a Cal Performances co-commission), I hope we get a chance to visit soon. (Violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja is this year's music director for the festival, and for those able to get down south, the whole schedule looks enticing.) Ah Young Hong and Kiera Duffy will be the two sopranos in the new work and Hersch himself will be on piano as part of an ensemble led by Muñoz. As you have probably guessed, I already have my ticket.

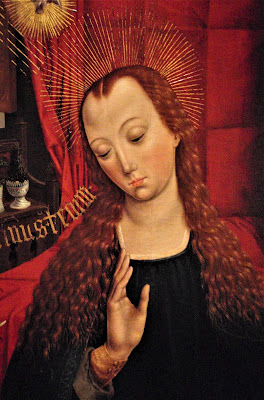

Museum Monday 2018/16

a detail of The Annunciation by the Master of the Retable of the Reyes Católicos at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco

I love her hand:

13 April 2018

Friday Photo 2018/15

Douglas Tilden's sculpture The Football Players on the campus of the University of California - Berkeley

09 April 2018

Museum Monday 2018/15

This elegant display of weapons from Africa is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, though I neglected to take a photo of the label so I don't have much more information

06 April 2018

02 April 2018

Museum Monday 2018/14

detail of The Charlatan by Tiepolo, which is normally found in the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya in Barcelona, but which I saw at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco as part of the exhibit Casanova: The Seduction of Europe, which is there until 28 May

01 April 2018

Whan That Aprille Day 2018

Since Whan That Aprille Day coincides with Easter this year, here is a tender Middle English religious poem in honor of both days. It seems like the sort of simple lyric you would teach a child as a prayer. In addition to the repetitions of sweet, Jesus is addressed throughout with the intimate thou/thee, creating a kindly sense of deep and personal devotion. There is a lovely pun on springe at the end, meaning grow but also suggesting the season when the earth renews itself.

I've interleaved a crib in italics. I found this poem in the Norton Critical Edition of Middle English Lyrics, edited by Maxwell S. Luria and Richard L. Hoffman. I've used their annotations as well as the glossary in the Penguin Classics edition of The Canterbury Tales.

Previous entries for Whan That Aprille Day can be found here, here, here, and also here.

Swete Jhesu, king of blisse,

Sweet Jesus, king of bliss,

Min herte love, min herte lisse,

My heart's love, my heart's joy,

Thou art swete, mid iwisse:

You are indeed sweet:

Wo is him that thee shall misse.

Woe to him who shall fail to find you.

Swete Jhesu, min herte light,

Sweet Jesus, my heart's light,

Thou art day withouten night.

You are day without a night.

Thou geve me strengthe and eke might

You give me strength and also the power

For to lovien thee all right.

To love you completely.

Swete Jhesu, my soule bote,

Sweet Jesus, my soul's remedy,

In min herte thou sette a rote

In my heart you plant a root

Of thy love that is so swote,

Of your love that is so sweet,

And wite it that it springe mote.

And guide it that it might grow.

detail of The Resurrection by an unknown artist active in Aragon in the first half of the fifteenth century, at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco

I've interleaved a crib in italics. I found this poem in the Norton Critical Edition of Middle English Lyrics, edited by Maxwell S. Luria and Richard L. Hoffman. I've used their annotations as well as the glossary in the Penguin Classics edition of The Canterbury Tales.

Previous entries for Whan That Aprille Day can be found here, here, here, and also here.

Swete Jhesu, king of blisse,

Sweet Jesus, king of bliss,

Min herte love, min herte lisse,

My heart's love, my heart's joy,

Thou art swete, mid iwisse:

You are indeed sweet:

Wo is him that thee shall misse.

Woe to him who shall fail to find you.

Swete Jhesu, min herte light,

Sweet Jesus, my heart's light,

Thou art day withouten night.

You are day without a night.

Thou geve me strengthe and eke might

You give me strength and also the power

For to lovien thee all right.

To love you completely.

Swete Jhesu, my soule bote,

Sweet Jesus, my soul's remedy,

In min herte thou sette a rote

In my heart you plant a root

Of thy love that is so swote,

Of your love that is so sweet,

And wite it that it springe mote.

And guide it that it might grow.

detail of The Resurrection by an unknown artist active in Aragon in the first half of the fifteenth century, at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)