I believe the show was touring because the collection is being transferred from the Brooklyn Museum to the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (check here for background on the collection and the move).

The show turned out to be wonderful. It's not inaccurate to call what we saw "fancy clothes for extremely rich women" but that doesn't really do it justice. Beyond simmering thoughts of class warfare – since we went on V's birthday, I promised her there would be no leftist fulminations from me on behalf of the proletariat; after all, it's not as if I could have had myself painted in a pious attitude in a corner of one of those altarpieces I love, either – the show was a dazzling display of color, form, texture, and ingenuity: painting in another form, or perhaps it was landscaping with cloth and thread.

There were large, somewhat ghostly period photographs of models wearing some of the clothes, which helped reinforce the sense of entering a different and vanished realm.

There were no men's clothes, and no everyday clothes for women, either, or even undergarments; this was a place where there was no everyday life, everything was a special event – a place of fantasy, where even practical necessities turned fanciful. Here are some shoes:

These are more like "sculptures for the feet."

I was not as vigilant as I usually am about photographing labels, so I'm not always sure who the designers are. I did get the label for the shoes below, since it was chockful of interesting information. These are part of the collection of Rita de Acosta Lydig (in a different room, on a different label, we found out that she was the sister of Mercedes de Acosta, an American playwright and poet who is best remembered – this was not on the labels – for affairs with many of the most glamorous and gifted women of mid-twentieth-century stage and screen, including Eva Le Gallienne, Garbo, Dietrich, Nazimova, and, according to rumor, several others, all famous and talented). She was the major client of Yantorny, who had his shoe-maker shop, excuse me I mean atelier, in the Place Vendôme in Paris. He had a sign in the window saying The Most Expensive Shoes in the World, which strikes me as extremely crude and vulgar; surely there was some more sophisticated coded way of saying this.

But he wasn't kidding; the initial deposit for a pair in 1913 was $600, which in today's currency (again, according to the label) would be approximately $10,000. Let me emphasize that that's just the down payment. He also included handmade shoe-trees, designed to be lightweight and hollow. This elaborate wooden carrying case held a dozen shoes, six pairs in each half, so basically it was holding almost double my annual salary (that's just "suggested retail price," without considering rarity, artistry, and historical interest).

But I can look at other artworks without being overly conscious of the cost: why are clothes different? Is it because they're something we all have to buy, in a way we do not have to buy altarpieces and bronzes? Is it some lingering notion that these applied arts are somehow lesser than the fine arts? Only the very rich could afford these items, but then that's true of most art. Was it just because the label brought it up so explicitly (as if to defuse the question)?

Once I got past that shoe label I thought less about money and more about art – actually, art history; it was fascinating to see how the items echoed and played off major artists and artistic movements of their time, starting with the flowing lines, rich colors, and peacock imagery of the Aesthetic Movement:

. . . and up to the tie-dyed 1970s (I think this one is by Yves St Laurent):

Classical Greece was an inspiration, as it has been for Western Art for centuries, and I thought about the neoclassical revival in music (the dress on the left below was one of my favorites):

But you could also see connections with the late-nineteenth / early-twentieth-century fascination with the circus:

and Surrealism:

There were non-Western influences as well, such as the rich colors and patterns of India:

Looking at the hats below, you can see one that was styled on Matisse's cutouts and another on Mondrian's blocks. But the one at far left was modeled on the kepi of the French military, the swirly black one was I think based on an African design, and the one on the bottom was inspired by an aircraft engine (or possibly the propeller). Mamie Eisenhower wore one of these aeronautical hats, which amused V. I think she had not expected such avant-garde styling from Mamie. The designers were wide-ranging and immersed in the world well beyond the little circle of their clientele.

Speaking of surrealists, here's Elsa Schiaparelli's "butterfly dress," the label for which read: "The butterfly, a symbol of transformation – and sometimes death – for the Surrealists, was a ubiquitous motif in Schiaparelli's work. She used it decoratively to represent beauty's emergence from the mundane. This icon expressed the designer's philosophy that chic clothes and a sense of style could transform the ordinary into the extraordinary." OK. Am I reading too much into it to find it amusing that the label-maker sees "chic clothes" and "a sense of style" as two separate things?

Anyway I like the butterflies, and particularly enjoyed seeing this dress against its backdrop photograph.

Next to the butterfly dress was another Schiaparelli, the swell little number below, which V loathed. I didn't mind it, and was entertained by her loathing, though I should note that my half-hearted attempts to defend it (because seriously, why should I defend it? what difference does it make to me?) ended up sounding slightly condescending to the dress: it's cute. It's fun. V was having none of it. She thought it was a rich woman mocking middle-class or agrarian women, and let the record show that I was not the one on this trip who brought up Marie Antoinette playing shepherdess. Who's an anarcho-syndicalist now, babe?

She particularly hated the pocket, which was one of the seed packets appliqued on the side. "Don't miss the pocket! Take a picture of that pocket!" I've known V almost forty years, and this is the closest I've come to hearing her actually hiss something.

Here's that pocket!:

Fun!

I thought one could accessorize the seed-packet dress with the Schiaparelli insect necklace below, but V was not buying it. "You don't make fun of farm women," was her final word on the matter.

I liked this necklace. The bugs are realistically molded, but painted in bright colors that make them, or at least some of them, look artificial. On their clear backing, it would look as if they were floating unsupported around your neck, to creepy and thrilling effect.

Still seething at Schiaparelli (a phrase I never, ever thought I would write), V was further irritated by the astrological symbols on the jacket below, though she was a bit mollified when a label said that the designer's use of planets and stars was a tribute to her beloved uncle, an astronomer (not astrologer), with whom she spent many childhood hours studying the nighttime skies. I also suggested to V that astrology was acceptable as a decorative motif, even for a math and science teacher like herself. I don't know if that helped.

We moved on from Schiaparelli. V liked the dress below very much.

Sometimes I became aware of how well the show was lit. The lights were generally dim, as they are for drawings or woodblock prints or other delicate works, in order to protect the fragile materials, but there were some effective spotlights.

The dress on the right below is called the "tart" dress. It looks quite respectable from this angle, and honestly my first, rather clueless, thought was "small pies? huh?" By process of elimination (no small pies were visible!) I realized that, yes, they meant the female kind of tart.

The name comes from the bold arrow-like inserts (red on the front, dark purple on the back) pointing up towards the breasts . . .

. . . and down towards the butt. (The dark purple below might show up a bit better if you can click to enlarge the photo.)

I forget the name of the woman who designed the tart dress, but she intended it as a feminist statement. I guess "being exploited for your sexuality" and "being 'empowered' by owning your sexuality" have been doing their little dance for quite some time. Nothing too surprising there. I thought the tart dress was stylish and bold, but honestly I'm not sure it's any more pointed than something like the Worth gown below, dated 1907 - 1910, which I photographed because it put me in mind of highly respectable females in the novels of Edith Wharton and Henry James. You can see that the neckline is quite low, and those flowing insert things (I think they were beaded) also underscore and draw attention to the breasts.

And you'd have to be a bold woman indeed to wear the dress below, inspired by the grandeur that was Greece and the glory that was Rome:

With a neckline like that, a red arrow would not really be necessary. You wouldn't even have fabric to put it on. (This is a different dress from the Grecian ones shown above.)

Though I was thinking a lot about different art movements while walking through the exhibit, I wasn't thinking that much about things like gender roles (that is most definitely not a complaint), because the slice of the world we're seeing here is so rarefied anyway, and these costumes (and that really is the right word) are so fanciful and often eccentrically individualistic. I'm not sure a woman could wear some of them twice – like the dress made out of huge poppies shown earlier; that sure struck me as a one-off.

But I guess the tiger dress below is meant as a sly comment on women as both predator and prey. I love tigers anyway, preferring them to lions, who always seem a bit worn out. We overheard one of the guards telling someone that the model in the backdrop photo, now an elderly woman, had come to see the show, and that she was incredibly charming and gracious. I felt oddly happy hearing that.

I'm really not sure what's going on with the big red flower on the dress below. Wouldn't it get in your way while you were reaching for a canapé? It seems sort of floppy and lopsided. I suggested to V that the dress would be improved if someone tore it off and she agreed. The big red flower was the only really egregiously puzzling thing we saw. Why did this seem like a good idea to the designer?

The dress below, however, struck me as cool (in every sense) and delightful; if it were blue and green instead of red I would consider it a perfect summer dress. It's almost like a superhero costume: if you're wearing this, you're marked out as someone with special powers, distinctive, not of this sweaty realm.

Since some consider the movies the great twentieth-century art form, it's not surprising that Hollywood and the fashion world played back and forth. The dress below, by the Fontana sisters of Italy, was worn by Ava Gardner in The Barefoot Contessa. In classic movie star style, she was apparently shorter than she looks on screen.

It seemed like something Columbina might wear in a really luxe Harlequinade, or an outfit Watteau would paint on a woman standing among the feathery leaves of shady melancholy trees.

The shoes and hats were all in vitrines, but only one of the dresses was: Charles James's Cloverleaf dress. There was a very interesting video in one of the rooms showing its elaborate construction. None of my photographs do it justice, as you really need an aerial view. The first one below gives you some idea of how it sweeps out in four distinct directions.

Here's a close-up of the lace. There were several versions of this dress, it seems, some of them in solid colors. This one was quite elaborate, with the lace and the rich fabric.

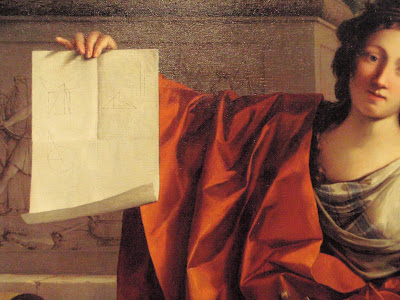

It was a triumph of engineering, and apparently James felt that way too. Seeing it and its mathematically produced elegance gave extra force to the Allegory of Geometry by Laurent de La Hyre (detail below) that we later saw in the baroque gallery.

Below is another James gown, the Siren. Some of the dresses had such a powerful presence that a mannequin would have lessened the aura. The frocks just stood there, absolute. I would do what this dress told me to do.

The gowns seemed to conjure up a whole vanished world of wit and elegance, a world that of course never existed: the women who wore these artworks were humans who would sweat, weep, defecate, struggle with or succumb to various appetites, who had blemishes, could get tired or sick, would grow old and die. These dresses were designed to float them above all that, at least temporarily, and above the rest of us. These fragile, easily damaged costumes seem monumental, like protective armor over fragile, easily damaged people.

When we left the exhibit it was actually raining outside, heavily enough so that we delayed leaving. Even a light rain is a remarkable thing to happen in California in early July, and though any precipitation is welcome during this drought, it seemed like another sign that larger unseen patterns were shifting around us.

After a brief walk to the bus stop, we hopped on the #1 California bus and headed to Chinatown, where we had a very enjoyable dinner, at a place we've gone to for years.

5 comments:

Lovely photo essay. And Charles James was some kind of serious, insane artist.

Thanks. Shortly before seeing this show I had coincidentally read a couple of articles about Charles James, maybe in the New Yorker and somewhere else?, and yeah: serious, insane artist.

Who is this V? She sounds very fussy.

It was a wonderful and memorable birthday. The photos are beautiful, and include details of many of my favorite things. There was so much there, so many things to think about that I didn't appreciate the beauty of the arrangements and lighting until I looked at your photos.

There is almost a generosity in wearing one of these pieces of clothing. The wearer must give herself up to the clothing, like a wall that gives itself up to an interesting painting. People notice the shoes or dress and not the wearer. I'm grateful that the wearers took good care of them and saved them, though they probably only wore them once.

Fussy? Not at all! She's a down-home gal who doesn't have time for certain kinds of foolishness, that's all. That may be "fussy" where you come from, but out here it's just plain common sense.

Glad you liked the photos, though I did wish I had a sharper camera.

I had over 200 and had to winnow them down and then do my usual cropping/adjusting etc so it took a while.

That's a very interesting point about giving yourself up to the dress -- we tend to think wearing couture is an ego thing, but really the dress would often overshadow the woman. So, yes, it's like making yourself a walking display case.

Wonderful! I was hanging on your every word! I love the way you write. Funny, thought-provoking, poetic descriptions of what looked to be a really fabulous show! I think I'll go back and read and enjoy it all over again! Thanks for sharing this!

Post a Comment