Satan enters the Serpent

[. . . ] through each Thicket Dank or Dry,

Like a black mist low creeping, he held on

His midnight search, where soonest he might find

The Serpent: him fast sleeping soon he found

In Labyrinth of many a round self-roll'd,

His head the midst, well stor'd with subtle wiles:

Not yet in horrid Shade or dismal Den,

Nor nocent yet, but on the grassy Herb

Fearless unfear'd he slept: in at his Mouth

The Devil enter'd, and his brutal sense,

In heart or head, possessing soon inspir'd

With act intelligential; but his sleep

Disturb'd not, waiting close th'approach of Morn.

Now when as sacred Light began to dawn

In Eden on the humid Flow'rs, that breath'd

Their morning Incense, when all things that breathe,

From th'Earth's great Altar send up silent praise

To the Creator, and his Nostrils fill

With grateful smell, forth came the human pair

And join'd their vocal Worship to the Choir

Of Creatures wanting voice [. . . .]

John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book IX, ll 179 - 199

After running snake-in-the-garden poems the past two weeks, I figured I might as well close out the summer with the ultimate Snake in the ultimate Garden, so here is an excerpt from Paradise Lost, and I have to say it's more difficult to grab an excerpt from that poem than you might think: Milton's verse is so fluid and flexible, and I kept thinking, Well, if I go back farther I can bring in that point or suggest that irony, and pretty soon you're typing out the whole book (though I have often spent my time in less productive and interesting ways).

Preceding this passage is one of those great and rhetorically complex speeches by Satan. These speeches often fool people, because they tend to take Satan at face value – this seems like an obviously reductive way to read the poem, but lots of people do it. I've heard some readers – actually, professors – mention their admiration for Satan's line in Book I "Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heav'n"; a sentiment which is fine as far as it goes, except it doesn't go any farther than Satan. One third of the angels followed him in rebellion (he later fudges the numbers, claiming that "wellnigh half" the angels followed him, which is not exactly a blatant lie but also not the clear truth), and those angels aren't reigning in Hell, they're serving there, which is surely worse than serving in Heaven. The line requires you to identify with Satan and forget that any one else is involved. But of course there's only one leader, one Satan; everyone else is just a generic fallen angel. And to accept that line at face value you'd also have to agree that what the angels are doing in Heaven is, in fact, serving, and that serving is inherently degrading. Satan is always deeply, deeply egocentric. (When considering Satan, it's useful to remember Milton's extensive political experience as part of the Puritan rebellion against the monarchy (he was almost executed after the Restoration).)

Satan is also the spirit of destruction, opposed to the creative bounty of God (a role emphasized by frequent references to God as "the Creator"). And it's typical of Satan that he ranks and judges Creation, rather than simply enjoying each thing for itself. He sees his entrance into the Serpent (despite the latter's reputation for subtlety, and his beauty as described later in the poem) as a "foul descent" and soliloquizes, "But what will not Ambition and Revenge / Descend to? who aspires must down as low / As high he soar'd. . . " Satan's speeches are carefully plotted, tracing the diminishment of his spirit as he sinks himself further into damnation.

This passage opens with Satan taking the form of a "black mist low creeping" in order to evade the angels on guard in Eden. He is on a "midnight search." Although night is often spoken of favorably by Milton, here it performs a more conventional function as a time of disguise and danger, in order to contrast it with "sacred Light," which is consistently identified with God (as in the opening of Book III: "Hail holy light, offspring of Heav'n first-born, / Or of th'eternal Coeternal beam / May I express thee unblam'd? since God is light / And never but in unapproached light / Dwelt from Eternity, dwelt then in thee, / Bright effluence of bright essence increate"). The mist reminds us that at the time of the poem's composition, mists were thought to be unhealthful. Low and creeping add to the scene's sense of horror, and our sense of the self-degradation of the once-mighty and magnificent Heavenly warrior.

Satan finds the object of his search, the Serpent, who is sleeping, his head in the middle of all his coils. This infolding circularity is described as a Labyrinth, which brings to mind the deadly monster, the Minotaur, in the middle of the original classical Labyrinth (there is a constant dialogue in Milton's epic between classical mythology and Christian belief). A labyrinth is also a confusing maze, filled with potential wrong paths, to be contrasted with the straight and narrow path that according to the gospels leads to salvation. As in Genesis, the serpent is described as the subtlest beast of the field, but neither Genesis nor Milton gives us any examples of the serpent's subtlety apart from Satan's actions through him (poor maligned Serpent!). This serpentine labyrinth is made of "many a round self-roll'd" – self-roll'd is part of the poem's on-going insistence on personal choice and responsibility (that is, free will); it's notable that the rebel angels are not actually thrown out of Heaven; instead, they choose to leap out of sheer terror when Messiah appears in his war-chariot during the battle in Heaven. Self-roll'd here is a subtle reinforcement of that theme, associating the Serpent and Satan with personally chosen confusion.

Another theme that is picked up in this passage is a sense of the impending Fall: throughout the poem we get Paradise, but hard on its heels is lost. So while the Serpent is still just another one of the delightful creatures in Eden (though with a head filled with wiles, which is one of the on-going indications that Paradise, far from being a state of antiseptic "perfection," is filled with the potential for its own destruction). So Milton defines the Serpent by what he is not yet: he does not yet hide in darkness, in dank crevices and other frightening places; he is not yet nocent (which is the opposite of innocent: that is, harmful, injurious, guilty). Phrasing it that way – he's not yet guilty – reminds us that he soon will be. Even before the Fall, the Serpent is seen retroactively, from the perspective of what he will soon become. This sense of the looming loss of innocence and goodness is part of what gives this epic, so much of which deals with heavenly and philosophical struggles, its poignant human power. For the time being, the Serpent is fearless and also not feared by other creatures.

The creeping black mist now enters the Serpent through his mouth: the first creature possessed by Satan. There is a pun on brutal: it refers to what used to be called "the brute beasts" (that is, the non-human creatures, those without language) but also carries its more usual modern sense of savage, hard, unpleasant. Satan in possession inspires the Serpent. This means fills him with the urge to do something, but it also means to breathe (from the Latin in spirare, to breathe into). Note later in the passage the importance of breath'd / breathe: two lines in a row end with these almost identical words, where they are associated with worship and with life itself. The use of inspire for the Serpent is part of the diabolical parody that runs through the poem, and sometimes we are introduced to the parody before we meet the celestial object of mockery (for example, we are introduced to the incestuous triangle of Satan, Sin, and Death before we meet its sacred counterpart, the Holy Trinity).

The night-scene of creeping terrors gives way to the sacred dawn. The unhealthy mist of Satan is contrasted with the humid (that is, dewy) flowers. As noted above, Satan's "inspiration" of the Serpent is contrasted with the peaceful breaths of Creation. Earth, in a beautiful image, is a great altar from which silent praise rises to the Creator (in contrast to this sacred and joyful unity, Satan resents any tribute paid to a power that isn't himself, and he is intent on destroying Paradise, simply because it isn't his). There is an echo of Biblical language in God's nostrils filling with the grateful smell of incense (grateful means both pleasing to the recipient and full of gratitude from the giver). The human pair come forth and give voice to the unlanguaged praise of the Garden and all of Creation, on this, the last day of their harmony.

I took this from the Signet Classic edition edited by Christopher Ricks, which is the one I usually carry around when I read this poem. The cover has changed several times since I started buying this edition; this version seems to be the latest.

31 August 2015

30 August 2015

Curious Flights: An English Portrait

Last night Curious Flights opened its second season with a wide-ranging concert in the recital hall of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Called An English Portrait, it featured mid-twentieth century English composers performed by a dazzling array of local talent. It's a tribute to Founder & Artistic Director Brenden Guy (who also played clarinet in several pieces) that he was able to gather so many excellent musicians for this fledgling group.

For the opening, soprano Julie Adams brought her rich, full voice and a lot of presence to John Ireland's Songs Sacred and Profane. She was a striking Blanche DuBois a couple of summers ago in Merola Opera's revival of Previn's A Streetcar Named Desire. Pianist Miles Graber accompanied her as they ranged over a variety of moods, from rough-and-tumble to poignant (that one, in the form of Song 4, The Salley Gardens, was my favorite). Her diction was good but it was still difficult to make out all the words, because that is what happens to words when they're sung by higher voices. And though the program-book was nicely put together and elegantly designed, it was spotty in its inclusion of song texts. It would have been helpful to have them for this set. I love that the evening featured less familiar pieces, but it's exactly that lack of familiarity that makes it helpful to have things like copies of the poems the composer has set. But that's a minor point, given the chance to luxuriate in this voice and music at close range.

There was a casual welcoming atmosphere to the evening but the Conservatory staff was commendably efficient in changing the stage set-up, which they had to do after each number, because of the smorgasbord of styles and formats. The second piece was the Rhapsodic Quintet by Herbert Howells; Brenden Guy in his role as clarinetist joined the One Found Sound string quartet in this enjoyable outburst of lyricism. The first half ended with three choral pieces by Finzi, Britten, and Vaughan Williams sung by the Schola Cantorum of St Dominic's Catholic Church, a part professional, mostly amateur chorus that gave a full presentation of their three pieces. The Finzi was My Spirit Sang All Day; the Britten was The Shepherd Carol, and the Vaughn Williams was Valiant for Truth. The Britten was a setting of a chorus from Auden's Christmas Oratorio, which he wrote for Britten though the composer only set a couple of its parts. The words are a sort of off-kilter combination of nursery-rhyme surrealism and whimsical adult disappointment. The four introductory verses are sung by individuals from the chorus, going up the voice rung (nice job from the quartet of soloists: bass Rhy Bidder, tenor Steve Ziegler, alto Heidi Waterman, and soprano Catherine Bither) and then the rest of the group joins in for the refrain. The Vaughn Williams is a setting of Mr Valiant-for-Truth's death from Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. As it proceeds through the piece the chorus sometimes thins out and sometimes joins in an exultatory togetherness, massing to terrific effect at the end, when the heavenly trumpets sound for him as he crosses to the other side. Texts for the Britten and Vaughn Williams were in the program, which was helpful. Having Auden appear really made me feel I was getting a more complete view of mid-century British cultural life.

The second half was made up of two big pieces, Arnold Bax's Sonata for Two Pianos and Britten's Sinfonietta, Op. 1. The Bax was performed by Peter Grunberg and Keisuke Nakagoshi. I could see a lot of visual contact between the two as they played, their pianos facing each other. There was a playful sense of camaraderie and friendly challenge that carried over into the music. There were many percussive effects in the piece (or maybe that's just how the piano increasingly sounds to me); the tender mid-section was my favorite. As with the rest of the program, you have to wonder why we don't get to hear this terrific piece more often.

The concluding Britten (and it's a fair measure of his stature and an important part of the evening's musical portrait of Britain that he was the only composer to have two pieces on the program) was conducted by John Kendall Bailey and performed by the Curious Flights Chamber Ensemble: Tess Varley and Baker Peeples on violin, Jason Pyszkowski on viola, Natalie Raney on cello, Eugene Theriault on double bass, Bethanne Walker on flute, Jesse Barrett on oboe, Brenden Guy on clarinet, Kristopher King on bassoon, and Mike Shuldes on horn. This is an early and very appealing work by Britten. Unfortunately the engaging performance was marred by a rude woman in the balcony who kept taking photographs, with a loud click-zip clearly audible each time. Other than that obnoxious behavior, the audience, as far as I could tell from where I sat, was courteous to the other audience members and the performers.

All in all, a successful start to Curious Flights's second season. Their next concert will be at the Century Club of California on Veterans Day and will feature violinist Madeleine Mitchell in music associated with the two world wars.

28 August 2015

25 August 2015

fun stuff I may or may not get to: September 2015

the BART warning

Here's this month's update on BART service interruptions (planned ones, that is; I don't claim any foreknowledge of the other kind). Tracks leading to the Transbay Tube need to be replaced, so over the Labor Day weekend (5 - 7 September) the West Oakland station will be closed and there will be no transbay service. There will be some buses from the 19th Street Oakland Station to the Transbay Terminal in San Francisco, but BART is basically hoping people will stay on whichever side of the bay they find themselves on after end of service on Friday. Trains will be running in San Francisco and in the East Bay; you just won't be able to take them from one to the other. Road traffic will no doubt increase considerably, especially since it's a long weekend. Check here for official updates.

And here's a little bonus August reminder, since I'm posting this before the end of the month: you can still get to the 29 August season opening concert for Curious Flights, featuring a lot of interesting music and many excellent performers, which you can read about here.

Theatrical

At Shotgun Players, Sarah Ruhl's Eurydice continues through 20 September. And as part of its Champagne Reading Series, Shotgun is presenting Letters from Cuba by Maria Irene Fornes, for two nights only, 21 - 22 September.

Berkeley Rep has the world premiere of a new musical based on the French film Amélie, with music by Daniel Messé, lyrics by Nathan Tysen and Daniel Messé, and book by Craig Lucas; that's 28 August to 4 October.

This season Custom Made Theatre is moving to 533 Sutter Street (at Powell, and easily accessible by a short walk up Union Square from the Powell Street BART station) and they are opening with Kenneth Lonergan's This Is Our Youth, running from 18 September to 17 October.

Modern/New Music

Stuff gets added to the Center for New Music schedule at odd times, so it's worth checking out their calendar more than once a month. There's a concert on 12 September that looks particularly interesting: I Sing Words: The Poetry Project, in which soprano Jill Morgan Brenner and pianist Anne Rainwater premiere art song collaborations between composer/poet teams (Danny Clay & Heather Christie, Joseph M. Colombo & J A Nowak, Kyle Hovatter & Matthew Zapruder, and Emma Logan & Chelsea Martin). I haven't heard the work of these artists, except for Kyle Hovatter, whose music I have enjoyed before.

Operatic

San Francisco Opera opens its fall season with two exciting shows: Verdi's Luisa Miller with rising young stars Leah Crocetto and Michael Fabiano and Sondheim's Sweeney Todd with Brian Mulligan, Stephanie Blythe, Elizabeth Futral, and Heidi Stober. I love Sweeney Todd so much that for many years it completely overshadowed for me everything else Sondheim has done in his long and brilliant career. It is one of the great American works for music-theater and I am thrilled to see it on the Opera House schedule. I only wish they had made it the opening night opera; it would be amusing to see if anyone in that particular audience got that they were being attacked. The dubious distinction of being wasted on the opening night audience goes instead to Luisa Miller; that's on 11 September so be forewarned. The other dates for Luisa are 16, 19, 22, 25, and 27 (matinee) September. The Sondheim is playing 12, 15, 18, 20 (matinee), 23, 26, and 29 September.

Also check out New Century Chamber Orchestra under Orchestral for a concert featuring the Letter Scene from Eugene Onegin.

Orchestral

New Century Chamber Orchestra kicks off its season with a program called Letters from Russia which includes the Letter Scene from Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin and Rachmaninoff's Vocalise, both sung by Ailyn Pérez, as well as works by Shostakovich, Pärt, and Jennifer Higdon, who is this season's featured composer. There is an open rehearsal the morning of 16 September and performances on 17 (Berkeley), 18 (Palo Alto), 19 (San Francisco), and 20 (San Rafael) September.

The California Symphony has a fun theme for its season opening concert: Passport to the World. Music Director Donato Cabrera leads the group in pieces by Gliere, Dvořák, Vaughan Williams, Elgar, Falla, Debussy, Sibelius, and Grieg. That's in Walnut Creek on 20 September at 4:00.

Cal Performances presents Gustavo Dudamel leading the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela in two Beethoven concerts: Symphonies 7 & 8 and the Egmont Overture on 24 September in Zellerbach Hall and the 9th on 25 September at the Greek Theater. The Zellerbach concert is almost sold out, but there seem to be a few seats available on-line – honestly, it looks close enough to sold out so that I almost didn't list it (why list something people can't buy a ticket to?) but just in case here are their "sold-out performance" procedures. There seem to be a fair number of seats still available for the Greek Theater concert. In addition to the concerts, there are some talks, films, master classes, and a symposium associated with the Orchestra's residency; you may check out the schedule for that here.

Baroque

Warren Stewart leads Magnificat in a Monteverdi program that features tenor Aaron Sheehan and soprano Christine Brandes in Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda on 25 (Palo Alto), 26 (Berkeley), and 27 (San Francisco, at 4:00) September.

Jazz

Cal Performances presents the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis on 18 September.

Visual Arts

J M W Turner: Painting Set Free is at the de Young Museum until 20 September, and it is not to be missed. The museum is out in Golden Gate Park, so depending on where you live it might be a bit of a schlep, but it's worth it for this show. It's unfortunate that the de Young does not have late night hours during the work week – OK, technically, that is not true; they are open late Fridays, but they turn the place into a wanna-be bar with very loud boring and annoying music, so if you want to look at art – which I would think would be the main reason for going to an art museum – you'll want to avoid the irritation and disappointment of dealing with their Friday nonsense.

Here's this month's update on BART service interruptions (planned ones, that is; I don't claim any foreknowledge of the other kind). Tracks leading to the Transbay Tube need to be replaced, so over the Labor Day weekend (5 - 7 September) the West Oakland station will be closed and there will be no transbay service. There will be some buses from the 19th Street Oakland Station to the Transbay Terminal in San Francisco, but BART is basically hoping people will stay on whichever side of the bay they find themselves on after end of service on Friday. Trains will be running in San Francisco and in the East Bay; you just won't be able to take them from one to the other. Road traffic will no doubt increase considerably, especially since it's a long weekend. Check here for official updates.

And here's a little bonus August reminder, since I'm posting this before the end of the month: you can still get to the 29 August season opening concert for Curious Flights, featuring a lot of interesting music and many excellent performers, which you can read about here.

Theatrical

At Shotgun Players, Sarah Ruhl's Eurydice continues through 20 September. And as part of its Champagne Reading Series, Shotgun is presenting Letters from Cuba by Maria Irene Fornes, for two nights only, 21 - 22 September.

Berkeley Rep has the world premiere of a new musical based on the French film Amélie, with music by Daniel Messé, lyrics by Nathan Tysen and Daniel Messé, and book by Craig Lucas; that's 28 August to 4 October.

This season Custom Made Theatre is moving to 533 Sutter Street (at Powell, and easily accessible by a short walk up Union Square from the Powell Street BART station) and they are opening with Kenneth Lonergan's This Is Our Youth, running from 18 September to 17 October.

Modern/New Music

Stuff gets added to the Center for New Music schedule at odd times, so it's worth checking out their calendar more than once a month. There's a concert on 12 September that looks particularly interesting: I Sing Words: The Poetry Project, in which soprano Jill Morgan Brenner and pianist Anne Rainwater premiere art song collaborations between composer/poet teams (Danny Clay & Heather Christie, Joseph M. Colombo & J A Nowak, Kyle Hovatter & Matthew Zapruder, and Emma Logan & Chelsea Martin). I haven't heard the work of these artists, except for Kyle Hovatter, whose music I have enjoyed before.

Operatic

San Francisco Opera opens its fall season with two exciting shows: Verdi's Luisa Miller with rising young stars Leah Crocetto and Michael Fabiano and Sondheim's Sweeney Todd with Brian Mulligan, Stephanie Blythe, Elizabeth Futral, and Heidi Stober. I love Sweeney Todd so much that for many years it completely overshadowed for me everything else Sondheim has done in his long and brilliant career. It is one of the great American works for music-theater and I am thrilled to see it on the Opera House schedule. I only wish they had made it the opening night opera; it would be amusing to see if anyone in that particular audience got that they were being attacked. The dubious distinction of being wasted on the opening night audience goes instead to Luisa Miller; that's on 11 September so be forewarned. The other dates for Luisa are 16, 19, 22, 25, and 27 (matinee) September. The Sondheim is playing 12, 15, 18, 20 (matinee), 23, 26, and 29 September.

Also check out New Century Chamber Orchestra under Orchestral for a concert featuring the Letter Scene from Eugene Onegin.

Orchestral

New Century Chamber Orchestra kicks off its season with a program called Letters from Russia which includes the Letter Scene from Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin and Rachmaninoff's Vocalise, both sung by Ailyn Pérez, as well as works by Shostakovich, Pärt, and Jennifer Higdon, who is this season's featured composer. There is an open rehearsal the morning of 16 September and performances on 17 (Berkeley), 18 (Palo Alto), 19 (San Francisco), and 20 (San Rafael) September.

The California Symphony has a fun theme for its season opening concert: Passport to the World. Music Director Donato Cabrera leads the group in pieces by Gliere, Dvořák, Vaughan Williams, Elgar, Falla, Debussy, Sibelius, and Grieg. That's in Walnut Creek on 20 September at 4:00.

Cal Performances presents Gustavo Dudamel leading the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela in two Beethoven concerts: Symphonies 7 & 8 and the Egmont Overture on 24 September in Zellerbach Hall and the 9th on 25 September at the Greek Theater. The Zellerbach concert is almost sold out, but there seem to be a few seats available on-line – honestly, it looks close enough to sold out so that I almost didn't list it (why list something people can't buy a ticket to?) but just in case here are their "sold-out performance" procedures. There seem to be a fair number of seats still available for the Greek Theater concert. In addition to the concerts, there are some talks, films, master classes, and a symposium associated with the Orchestra's residency; you may check out the schedule for that here.

Baroque

Warren Stewart leads Magnificat in a Monteverdi program that features tenor Aaron Sheehan and soprano Christine Brandes in Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda on 25 (Palo Alto), 26 (Berkeley), and 27 (San Francisco, at 4:00) September.

Jazz

Cal Performances presents the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis on 18 September.

Visual Arts

J M W Turner: Painting Set Free is at the de Young Museum until 20 September, and it is not to be missed. The museum is out in Golden Gate Park, so depending on where you live it might be a bit of a schlep, but it's worth it for this show. It's unfortunate that the de Young does not have late night hours during the work week – OK, technically, that is not true; they are open late Fridays, but they turn the place into a wanna-be bar with very loud boring and annoying music, so if you want to look at art – which I would think would be the main reason for going to an art museum – you'll want to avoid the irritation and disappointment of dealing with their Friday nonsense.

Tomato Tuesday 2015/16

Just a brief update this week, as there is not much new to report – no cat sightings, no sudden ripeness; it's all just starting to slide towards the end. I didn't get out into the yard much this weekend because I felt sort of listless and my head hurt (possibly an early sign of my typical September allergies, arriving earlier than usual thanks to climate change). The obnoxious people living behind me had some kind of loud gathering on Sunday and I didn't feel like dealing with that either.

I've had a few more of the Michael Pollans (on the left above and in the two shots below).

There are currently eleven fruits in various stages of ripeness hanging from its vines. Only one looks about ready to go. I ate the other ripe ones, as reported last week. I did share a couple as well.

Cherokee Purple (on the right in the top photo, flopping to one side, and in the two below) now has seventeen fruits on it, all of them in various shades of red ripeness except for the one green one you can see in the bottom shot. It's been a long time coming, but it does look as if it will come through with a fair number of tomatoes for me.

I did actually pick a few of those this evening (I'm writing this Monday night) but have not had a chance to try them. I got home much later than usual because the trains were snarled up for hours. I heard later that there was a suicide on the tracks.

That seems to be happening more and more often. Take care of yourself, people. Be considerate of each other. Try to make the best of things.

24 August 2015

Poem of the Week 2015/34

The Compost Heap

It waxed with autumn, when the leaves –

Dogwood, oak, and sycamore –

Avalanched the yard and slipped

Like unpaid bills beneath the door.

In winter it gave off a warmth

And held its ground against the snow,

The barrow of the buried year,

The swelling that spring stirred below.

In summer, we'd identify

The volunteers and green recruits,

A sapling apple or a pear

That stemmed from bruised or bitten fruits.

And everything we threw away

And we forgot, would by and by

Return to earth, or drop its seed

Take root and start to ramify.

We left the garden in the fall –

You turned the heap up with the rake

And startled latent in its heart

The dark glissando of a snake.

A E Stallings

Last week's snake poem reminded me of this one. Also, late August is the time of year when the leaves start dropping more thoroughly and my outdoor energies turn from growing and harvesting to raking and sweeping up and filling my own compost bin (and then seeing the driveway and front yard covered within minutes with newly fallen leaves, as if I hadn't done a thing; it's a useful life lesson).

On the surface of this elegant, unsettling poem, Stallings is describing an ordinary compost heap. She steps us through the seasonal life of this pile of garden discards: first the falling leaves of autumn, specified by variety, so we can tell the speaker is conversant with the natural world. They fall like an avalanche in the yard, and are so abundant they slide under the doors, like a notice from a bill collector insistent on an overdue payment. Just the usual piles of autumn leaves, but already there are threatening intimations, both grand (an avalanche!) and domestic (money owed that you can't pay). The poem proceeds by a series of double meanings, which slowly build up a sense of unease; we're never quite where we think we are, once we take a closer look.

The second quatrain covers winter and spring. The compost generates heat as it decomposes, enough to keep off the snow, but only enough to "hold its ground" – that is, both the actual ground covered by the compost pile and ground in the sense of to hold one's own. It's not warming anyone else; it's just keeping itself functioning (that is, decomposing) in the snow. The pile is "the barrow of the buried year" – on the one hand, it is like the wheelbarrow possibly used to bring the swept-up leaves over to the mound, a stationary heap of last year's leaves. But a barrow can also mean an ancient burial mound, and in that sense the compost pile is where the dead year is buried. So again the witty metaphors carry with them intimations of barely hanging on and even of death.

Notice the poet's light touch with alliteration, which helps the music of her verse: in the first line, winter / warmth; in the second line, barrow / buried; in the final line, spring brings an expansive use of three words linked by alliteration: swelling / spring / stirred.

The third quatrain moves on to summer. Earlier the it of the compost pile predominated, but in summer there are fewer leaves being added and suddenly the focus shifts to a we: the garden is now inhabited. We are identifying "the volunteers and green recruits." Again, there are double meanings: in a garden, a volunteer is something you didn't deliberately plant, but that grew on its own, propagated by breezes or birds or walked into the garden on your shoes or by some similar method. But volunteer also sounds like someone who has offered to do something, and here the volunteers sound like soldiers, coupled as they are with green recruits: green obviously refers to the color of most plants, but it can also mean new or inexperienced. (Perhaps these novice soldiers are more likely to be killed or maimed in battle? Is this another subtle suggestion of future disaster?) Recruits not only puns off volunteers but has its origin in the Latin recrescere (to grow again), which has obvious relevance to a garden in summer and to the compost pile, in which old things break down into new and fertile ground. (In case the Latin seems like a stretch: Stallings is a classicist who has also translated Lucretius's De rerum natura / The Nature of Things, so I think it's a safe bet that she would be aware of the etymology here.)

Looking back at this third quatrain after we've finished the poem and discovered the snake in the garden (which inevitably brings up the image of Satan as a snake in the Garden of Paradise), it seems likely that the appearance of the apple here, stemming (note also the pun on stem, which means both the cause or origin of something and part of a plant) from bruised or bitten fruit, is another echo of the story of the Fall. Adam and Eve transgressed by biting the forbidden fruit, and bruised might bring to mind Genesis 3:15, in which God punishes the Snake: "And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel." (Seed also links back to the garden theme; you can really go down the rabbit-hole investigating the implications of these words.) Perhaps pear is the second named fruit to bring up a pun on pair, either Adam and Eve or the we who have appeared in this quatrain.

The very specific descriptions of the garden we've seen so far – the particular leaves, the types of fruit, the life-cycle of a compost heap – give way in the fourth quatrain to more general descriptions of things "we threw away / and we forgot"; she's still talking about the garden, of course, but the sudden move away from specifics to generalities gives these lines larger emotional implications and suggest something about the life that "we" were living. (I should point out that I do not know anything about Stallings's life beyond a few very basic facts from her author bio; anything I say here is how I'm reading the speaker of the poem, not the life of the actual person who wrote it.) There's something careless, heedless, about We; their garden is not a place of memory or harvest (except for the sort-of harvest of the compost heap); they lose things, they discard them, they forget. But the earth does not forget. Everything (she has clearly stated everything) returns to earth (that is, decomposes, as in the compost pile) or sprouts into a new plant: everything dies, everything is reborn. Return to earth and drop its seed both have Biblical echoes to my ears, perhaps connecting back with other hints to the story of the Fall. These casual, forgotten things take root and also ramify: that is, branch out, spread, form offshoots, but the word also brings to mind ramifications, as in the consequences of actions or events. In other words: these things, discarded and forgotten as they may be, are never truly gone; they are buried deep, they burrow up, they spread out. And then we have to figure out what they are and where they came from, much as the volunteer saplings in the compost can be traced back to a forgotten piece of fruit. And then we have to deal with the consequences.

The first line of the fifth quatrain, We left the garden in the fall, is, on its surface, a simple statement of fact (we moved away then), but metaphorically it clearly references the story of Paradise lost; fall is autumn, but also The Fall of Humanity, a theme which culminates in the final word of the poem, when the compost pile reveals a hitherto hidden snake. And not just hidden, but latent in its heart, as if it were always potentially there, just waiting to be revealed. (Obviously, the use of heart to refer to the center of the pile also implicates the human heart). The discovery is startling for both snake and speaker: among their heedlessness, the reptilian presence has brought them up short with the knowledge of what they've been nurturing unawares.

Glissando is such a lovely word here. It is a musical term referring to "a rapid slide through a series of consecutive tones in a scalelike passage" (definition from the American Heritage Dictionary). This sound effect (a sudden burst of music in a hitherto silent garden, a sudden splash on the sound track) replicates both the movement of a startled snake and the frisson that sweeps your nerves when you startle a snake. There's also a nice little serpentine hiss built into glissando.

The snake, the dark secret hidden in the compost pile, doesn't appear until the very last word; when it surfaces, it brings with it the uneasy intimations that have been running through the entire poem. Snake appears and rhymes with rake: a coincidence? or a pun on rake meaning a dissolute or promiscuous man? Is there a hint there explaining why We left the garden in the fall? It seems like a far reach, but by this point in the poem we're used to casual phrases collapsing into troubling implications. This verbal technique creates a gathering sense of unease beneath the music of the poem. We are heedless, we forget; but the earth remembers, and, like an insistent collector bent on exacting what we owe, will slip his bills under our unaware doors. But there is a suggestion of possible renewal, too, in the ongoing process of decay and rebirth in the compost pile.

This is from the collection Olives by A E Stallings.

It waxed with autumn, when the leaves –

Dogwood, oak, and sycamore –

Avalanched the yard and slipped

Like unpaid bills beneath the door.

In winter it gave off a warmth

And held its ground against the snow,

The barrow of the buried year,

The swelling that spring stirred below.

In summer, we'd identify

The volunteers and green recruits,

A sapling apple or a pear

That stemmed from bruised or bitten fruits.

And everything we threw away

And we forgot, would by and by

Return to earth, or drop its seed

Take root and start to ramify.

We left the garden in the fall –

You turned the heap up with the rake

And startled latent in its heart

The dark glissando of a snake.

A E Stallings

Last week's snake poem reminded me of this one. Also, late August is the time of year when the leaves start dropping more thoroughly and my outdoor energies turn from growing and harvesting to raking and sweeping up and filling my own compost bin (and then seeing the driveway and front yard covered within minutes with newly fallen leaves, as if I hadn't done a thing; it's a useful life lesson).

On the surface of this elegant, unsettling poem, Stallings is describing an ordinary compost heap. She steps us through the seasonal life of this pile of garden discards: first the falling leaves of autumn, specified by variety, so we can tell the speaker is conversant with the natural world. They fall like an avalanche in the yard, and are so abundant they slide under the doors, like a notice from a bill collector insistent on an overdue payment. Just the usual piles of autumn leaves, but already there are threatening intimations, both grand (an avalanche!) and domestic (money owed that you can't pay). The poem proceeds by a series of double meanings, which slowly build up a sense of unease; we're never quite where we think we are, once we take a closer look.

The second quatrain covers winter and spring. The compost generates heat as it decomposes, enough to keep off the snow, but only enough to "hold its ground" – that is, both the actual ground covered by the compost pile and ground in the sense of to hold one's own. It's not warming anyone else; it's just keeping itself functioning (that is, decomposing) in the snow. The pile is "the barrow of the buried year" – on the one hand, it is like the wheelbarrow possibly used to bring the swept-up leaves over to the mound, a stationary heap of last year's leaves. But a barrow can also mean an ancient burial mound, and in that sense the compost pile is where the dead year is buried. So again the witty metaphors carry with them intimations of barely hanging on and even of death.

Notice the poet's light touch with alliteration, which helps the music of her verse: in the first line, winter / warmth; in the second line, barrow / buried; in the final line, spring brings an expansive use of three words linked by alliteration: swelling / spring / stirred.

The third quatrain moves on to summer. Earlier the it of the compost pile predominated, but in summer there are fewer leaves being added and suddenly the focus shifts to a we: the garden is now inhabited. We are identifying "the volunteers and green recruits." Again, there are double meanings: in a garden, a volunteer is something you didn't deliberately plant, but that grew on its own, propagated by breezes or birds or walked into the garden on your shoes or by some similar method. But volunteer also sounds like someone who has offered to do something, and here the volunteers sound like soldiers, coupled as they are with green recruits: green obviously refers to the color of most plants, but it can also mean new or inexperienced. (Perhaps these novice soldiers are more likely to be killed or maimed in battle? Is this another subtle suggestion of future disaster?) Recruits not only puns off volunteers but has its origin in the Latin recrescere (to grow again), which has obvious relevance to a garden in summer and to the compost pile, in which old things break down into new and fertile ground. (In case the Latin seems like a stretch: Stallings is a classicist who has also translated Lucretius's De rerum natura / The Nature of Things, so I think it's a safe bet that she would be aware of the etymology here.)

Looking back at this third quatrain after we've finished the poem and discovered the snake in the garden (which inevitably brings up the image of Satan as a snake in the Garden of Paradise), it seems likely that the appearance of the apple here, stemming (note also the pun on stem, which means both the cause or origin of something and part of a plant) from bruised or bitten fruit, is another echo of the story of the Fall. Adam and Eve transgressed by biting the forbidden fruit, and bruised might bring to mind Genesis 3:15, in which God punishes the Snake: "And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel." (Seed also links back to the garden theme; you can really go down the rabbit-hole investigating the implications of these words.) Perhaps pear is the second named fruit to bring up a pun on pair, either Adam and Eve or the we who have appeared in this quatrain.

The very specific descriptions of the garden we've seen so far – the particular leaves, the types of fruit, the life-cycle of a compost heap – give way in the fourth quatrain to more general descriptions of things "we threw away / and we forgot"; she's still talking about the garden, of course, but the sudden move away from specifics to generalities gives these lines larger emotional implications and suggest something about the life that "we" were living. (I should point out that I do not know anything about Stallings's life beyond a few very basic facts from her author bio; anything I say here is how I'm reading the speaker of the poem, not the life of the actual person who wrote it.) There's something careless, heedless, about We; their garden is not a place of memory or harvest (except for the sort-of harvest of the compost heap); they lose things, they discard them, they forget. But the earth does not forget. Everything (she has clearly stated everything) returns to earth (that is, decomposes, as in the compost pile) or sprouts into a new plant: everything dies, everything is reborn. Return to earth and drop its seed both have Biblical echoes to my ears, perhaps connecting back with other hints to the story of the Fall. These casual, forgotten things take root and also ramify: that is, branch out, spread, form offshoots, but the word also brings to mind ramifications, as in the consequences of actions or events. In other words: these things, discarded and forgotten as they may be, are never truly gone; they are buried deep, they burrow up, they spread out. And then we have to figure out what they are and where they came from, much as the volunteer saplings in the compost can be traced back to a forgotten piece of fruit. And then we have to deal with the consequences.

The first line of the fifth quatrain, We left the garden in the fall, is, on its surface, a simple statement of fact (we moved away then), but metaphorically it clearly references the story of Paradise lost; fall is autumn, but also The Fall of Humanity, a theme which culminates in the final word of the poem, when the compost pile reveals a hitherto hidden snake. And not just hidden, but latent in its heart, as if it were always potentially there, just waiting to be revealed. (Obviously, the use of heart to refer to the center of the pile also implicates the human heart). The discovery is startling for both snake and speaker: among their heedlessness, the reptilian presence has brought them up short with the knowledge of what they've been nurturing unawares.

Glissando is such a lovely word here. It is a musical term referring to "a rapid slide through a series of consecutive tones in a scalelike passage" (definition from the American Heritage Dictionary). This sound effect (a sudden burst of music in a hitherto silent garden, a sudden splash on the sound track) replicates both the movement of a startled snake and the frisson that sweeps your nerves when you startle a snake. There's also a nice little serpentine hiss built into glissando.

The snake, the dark secret hidden in the compost pile, doesn't appear until the very last word; when it surfaces, it brings with it the uneasy intimations that have been running through the entire poem. Snake appears and rhymes with rake: a coincidence? or a pun on rake meaning a dissolute or promiscuous man? Is there a hint there explaining why We left the garden in the fall? It seems like a far reach, but by this point in the poem we're used to casual phrases collapsing into troubling implications. This verbal technique creates a gathering sense of unease beneath the music of the poem. We are heedless, we forget; but the earth remembers, and, like an insistent collector bent on exacting what we owe, will slip his bills under our unaware doors. But there is a suggestion of possible renewal, too, in the ongoing process of decay and rebirth in the compost pile.

This is from the collection Olives by A E Stallings.

22 August 2015

The Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at the Legion of Honor

I have a troubled relationship with Fashion – some would say it's because we've never met, which isn't quite true – so I was not really sure what to expect when V and I headed out to the Legion of Honor in early July to see the exhibit High Style: The Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection.

I believe the show was touring because the collection is being transferred from the Brooklyn Museum to the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (check here for background on the collection and the move).

The show turned out to be wonderful. It's not inaccurate to call what we saw "fancy clothes for extremely rich women" but that doesn't really do it justice. Beyond simmering thoughts of class warfare – since we went on V's birthday, I promised her there would be no leftist fulminations from me on behalf of the proletariat; after all, it's not as if I could have had myself painted in a pious attitude in a corner of one of those altarpieces I love, either – the show was a dazzling display of color, form, texture, and ingenuity: painting in another form, or perhaps it was landscaping with cloth and thread.

There were large, somewhat ghostly period photographs of models wearing some of the clothes, which helped reinforce the sense of entering a different and vanished realm.

There were no men's clothes, and no everyday clothes for women, either, or even undergarments; this was a place where there was no everyday life, everything was a special event – a place of fantasy, where even practical necessities turned fanciful. Here are some shoes:

These are more like "sculptures for the feet."

I was not as vigilant as I usually am about photographing labels, so I'm not always sure who the designers are. I did get the label for the shoes below, since it was chockful of interesting information. These are part of the collection of Rita de Acosta Lydig (in a different room, on a different label, we found out that she was the sister of Mercedes de Acosta, an American playwright and poet who is best remembered – this was not on the labels – for affairs with many of the most glamorous and gifted women of mid-twentieth-century stage and screen, including Eva Le Gallienne, Garbo, Dietrich, Nazimova, and, according to rumor, several others, all famous and talented). She was the major client of Yantorny, who had his shoe-maker shop, excuse me I mean atelier, in the Place Vendôme in Paris. He had a sign in the window saying The Most Expensive Shoes in the World, which strikes me as extremely crude and vulgar; surely there was some more sophisticated coded way of saying this.

But he wasn't kidding; the initial deposit for a pair in 1913 was $600, which in today's currency (again, according to the label) would be approximately $10,000. Let me emphasize that that's just the down payment. He also included handmade shoe-trees, designed to be lightweight and hollow. This elaborate wooden carrying case held a dozen shoes, six pairs in each half, so basically it was holding almost double my annual salary (that's just "suggested retail price," without considering rarity, artistry, and historical interest).

But I can look at other artworks without being overly conscious of the cost: why are clothes different? Is it because they're something we all have to buy, in a way we do not have to buy altarpieces and bronzes? Is it some lingering notion that these applied arts are somehow lesser than the fine arts? Only the very rich could afford these items, but then that's true of most art. Was it just because the label brought it up so explicitly (as if to defuse the question)?

Once I got past that shoe label I thought less about money and more about art – actually, art history; it was fascinating to see how the items echoed and played off major artists and artistic movements of their time, starting with the flowing lines, rich colors, and peacock imagery of the Aesthetic Movement:

. . . and up to the tie-dyed 1970s (I think this one is by Yves St Laurent):

Classical Greece was an inspiration, as it has been for Western Art for centuries, and I thought about the neoclassical revival in music (the dress on the left below was one of my favorites):

But you could also see connections with the late-nineteenth / early-twentieth-century fascination with the circus:

and Surrealism:

There were non-Western influences as well, such as the rich colors and patterns of India:

Looking at the hats below, you can see one that was styled on Matisse's cutouts and another on Mondrian's blocks. But the one at far left was modeled on the kepi of the French military, the swirly black one was I think based on an African design, and the one on the bottom was inspired by an aircraft engine (or possibly the propeller). Mamie Eisenhower wore one of these aeronautical hats, which amused V. I think she had not expected such avant-garde styling from Mamie. The designers were wide-ranging and immersed in the world well beyond the little circle of their clientele.

Speaking of surrealists, here's Elsa Schiaparelli's "butterfly dress," the label for which read: "The butterfly, a symbol of transformation – and sometimes death – for the Surrealists, was a ubiquitous motif in Schiaparelli's work. She used it decoratively to represent beauty's emergence from the mundane. This icon expressed the designer's philosophy that chic clothes and a sense of style could transform the ordinary into the extraordinary." OK. Am I reading too much into it to find it amusing that the label-maker sees "chic clothes" and "a sense of style" as two separate things?

Anyway I like the butterflies, and particularly enjoyed seeing this dress against its backdrop photograph.

Next to the butterfly dress was another Schiaparelli, the swell little number below, which V loathed. I didn't mind it, and was entertained by her loathing, though I should note that my half-hearted attempts to defend it (because seriously, why should I defend it? what difference does it make to me?) ended up sounding slightly condescending to the dress: it's cute. It's fun. V was having none of it. She thought it was a rich woman mocking middle-class or agrarian women, and let the record show that I was not the one on this trip who brought up Marie Antoinette playing shepherdess. Who's an anarcho-syndicalist now, babe?

Still seething at Schiaparelli (a phrase I never, ever thought I would write), V was further irritated by the astrological symbols on the jacket below, though she was a bit mollified when a label said that the designer's use of planets and stars was a tribute to her beloved uncle, an astronomer (not astrologer), with whom she spent many childhood hours studying the nighttime skies. I also suggested to V that astrology was acceptable as a decorative motif, even for a math and science teacher like herself. I don't know if that helped.

We moved on from Schiaparelli. V liked the dress below very much.

The name comes from the bold arrow-like inserts (red on the front, dark purple on the back) pointing up towards the breasts . . .

. . . and down towards the butt. (The dark purple below might show up a bit better if you can click to enlarge the photo.)

I forget the name of the woman who designed the tart dress, but she intended it as a feminist statement. I guess "being exploited for your sexuality" and "being 'empowered' by owning your sexuality" have been doing their little dance for quite some time. Nothing too surprising there. I thought the tart dress was stylish and bold, but honestly I'm not sure it's any more pointed than something like the Worth gown below, dated 1907 - 1910, which I photographed because it put me in mind of highly respectable females in the novels of Edith Wharton and Henry James. You can see that the neckline is quite low, and those flowing insert things (I think they were beaded) also underscore and draw attention to the breasts.

And you'd have to be a bold woman indeed to wear the dress below, inspired by the grandeur that was Greece and the glory that was Rome:

With a neckline like that, a red arrow would not really be necessary. You wouldn't even have fabric to put it on. (This is a different dress from the Grecian ones shown above.)

Though I was thinking a lot about different art movements while walking through the exhibit, I wasn't thinking that much about things like gender roles (that is most definitely not a complaint), because the slice of the world we're seeing here is so rarefied anyway, and these costumes (and that really is the right word) are so fanciful and often eccentrically individualistic. I'm not sure a woman could wear some of them twice – like the dress made out of huge poppies shown earlier; that sure struck me as a one-off.

But I guess the tiger dress below is meant as a sly comment on women as both predator and prey. I love tigers anyway, preferring them to lions, who always seem a bit worn out. We overheard one of the guards telling someone that the model in the backdrop photo, now an elderly woman, had come to see the show, and that she was incredibly charming and gracious. I felt oddly happy hearing that.

I'm really not sure what's going on with the big red flower on the dress below. Wouldn't it get in your way while you were reaching for a canapé? It seems sort of floppy and lopsided. I suggested to V that the dress would be improved if someone tore it off and she agreed. The big red flower was the only really egregiously puzzling thing we saw. Why did this seem like a good idea to the designer?

Many of the gowns in the last couple of rooms were by American designer Charles James. Below is his Ribbon dress from 1946. The construction of the skirt, with its variety of colors, forced a fuller silhouette on the hips, which is why V did not like this dress, as she felt it accentuated them in a way that would be unflattering for most women. (It was designed with a particular client in mind, who was described in such glowing terms – her intelligence, her taste, her daring – that I wanted to see a portrait of her, but there was none; the dress stood on its own without its intended occupant.) Maybe it was that sort of farthingale thing going on in the hips that brought to mind an earlier century and a theatrical setting; I liked this dress and its colors and subtly contrasting textures and it put me in mind of the commedia dell'arte.

It seemed like something Columbina might wear in a really luxe Harlequinade, or an outfit Watteau would paint on a woman standing among the feathery leaves of shady melancholy trees.

The shoes and hats were all in vitrines, but only one of the dresses was: Charles James's Cloverleaf dress. There was a very interesting video in one of the rooms showing its elaborate construction. None of my photographs do it justice, as you really need an aerial view. The first one below gives you some idea of how it sweeps out in four distinct directions.

Here's a close-up of the lace. There were several versions of this dress, it seems, some of them in solid colors. This one was quite elaborate, with the lace and the rich fabric.

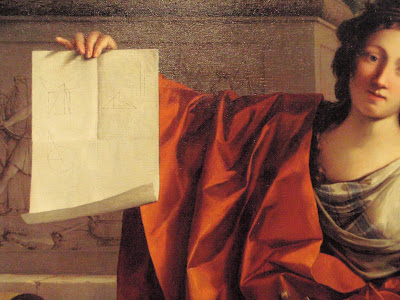

It was a triumph of engineering, and apparently James felt that way too. Seeing it and its mathematically produced elegance gave extra force to the Allegory of Geometry by Laurent de La Hyre (detail below) that we later saw in the baroque gallery.

The gowns seemed to conjure up a whole vanished world of wit and elegance, a world that of course never existed: the women who wore these artworks were humans who would sweat, weep, defecate, struggle with or succumb to various appetites, who had blemishes, could get tired or sick, would grow old and die. These dresses were designed to float them above all that, at least temporarily, and above the rest of us. These fragile, easily damaged costumes seem monumental, like protective armor over fragile, easily damaged people.

This phantom world was evoked so splendidly that after a while I began to wonder if actually we were the ones who were ghosts, flitting through a borrowed world and then vanishing unregarded.

I believe the show was touring because the collection is being transferred from the Brooklyn Museum to the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (check here for background on the collection and the move).

The show turned out to be wonderful. It's not inaccurate to call what we saw "fancy clothes for extremely rich women" but that doesn't really do it justice. Beyond simmering thoughts of class warfare – since we went on V's birthday, I promised her there would be no leftist fulminations from me on behalf of the proletariat; after all, it's not as if I could have had myself painted in a pious attitude in a corner of one of those altarpieces I love, either – the show was a dazzling display of color, form, texture, and ingenuity: painting in another form, or perhaps it was landscaping with cloth and thread.

There were large, somewhat ghostly period photographs of models wearing some of the clothes, which helped reinforce the sense of entering a different and vanished realm.

There were no men's clothes, and no everyday clothes for women, either, or even undergarments; this was a place where there was no everyday life, everything was a special event – a place of fantasy, where even practical necessities turned fanciful. Here are some shoes:

These are more like "sculptures for the feet."

I was not as vigilant as I usually am about photographing labels, so I'm not always sure who the designers are. I did get the label for the shoes below, since it was chockful of interesting information. These are part of the collection of Rita de Acosta Lydig (in a different room, on a different label, we found out that she was the sister of Mercedes de Acosta, an American playwright and poet who is best remembered – this was not on the labels – for affairs with many of the most glamorous and gifted women of mid-twentieth-century stage and screen, including Eva Le Gallienne, Garbo, Dietrich, Nazimova, and, according to rumor, several others, all famous and talented). She was the major client of Yantorny, who had his shoe-maker shop, excuse me I mean atelier, in the Place Vendôme in Paris. He had a sign in the window saying The Most Expensive Shoes in the World, which strikes me as extremely crude and vulgar; surely there was some more sophisticated coded way of saying this.

But he wasn't kidding; the initial deposit for a pair in 1913 was $600, which in today's currency (again, according to the label) would be approximately $10,000. Let me emphasize that that's just the down payment. He also included handmade shoe-trees, designed to be lightweight and hollow. This elaborate wooden carrying case held a dozen shoes, six pairs in each half, so basically it was holding almost double my annual salary (that's just "suggested retail price," without considering rarity, artistry, and historical interest).

But I can look at other artworks without being overly conscious of the cost: why are clothes different? Is it because they're something we all have to buy, in a way we do not have to buy altarpieces and bronzes? Is it some lingering notion that these applied arts are somehow lesser than the fine arts? Only the very rich could afford these items, but then that's true of most art. Was it just because the label brought it up so explicitly (as if to defuse the question)?

Once I got past that shoe label I thought less about money and more about art – actually, art history; it was fascinating to see how the items echoed and played off major artists and artistic movements of their time, starting with the flowing lines, rich colors, and peacock imagery of the Aesthetic Movement:

. . . and up to the tie-dyed 1970s (I think this one is by Yves St Laurent):

Classical Greece was an inspiration, as it has been for Western Art for centuries, and I thought about the neoclassical revival in music (the dress on the left below was one of my favorites):

But you could also see connections with the late-nineteenth / early-twentieth-century fascination with the circus:

and Surrealism:

There were non-Western influences as well, such as the rich colors and patterns of India:

Looking at the hats below, you can see one that was styled on Matisse's cutouts and another on Mondrian's blocks. But the one at far left was modeled on the kepi of the French military, the swirly black one was I think based on an African design, and the one on the bottom was inspired by an aircraft engine (or possibly the propeller). Mamie Eisenhower wore one of these aeronautical hats, which amused V. I think she had not expected such avant-garde styling from Mamie. The designers were wide-ranging and immersed in the world well beyond the little circle of their clientele.

Speaking of surrealists, here's Elsa Schiaparelli's "butterfly dress," the label for which read: "The butterfly, a symbol of transformation – and sometimes death – for the Surrealists, was a ubiquitous motif in Schiaparelli's work. She used it decoratively to represent beauty's emergence from the mundane. This icon expressed the designer's philosophy that chic clothes and a sense of style could transform the ordinary into the extraordinary." OK. Am I reading too much into it to find it amusing that the label-maker sees "chic clothes" and "a sense of style" as two separate things?

Anyway I like the butterflies, and particularly enjoyed seeing this dress against its backdrop photograph.

Next to the butterfly dress was another Schiaparelli, the swell little number below, which V loathed. I didn't mind it, and was entertained by her loathing, though I should note that my half-hearted attempts to defend it (because seriously, why should I defend it? what difference does it make to me?) ended up sounding slightly condescending to the dress: it's cute. It's fun. V was having none of it. She thought it was a rich woman mocking middle-class or agrarian women, and let the record show that I was not the one on this trip who brought up Marie Antoinette playing shepherdess. Who's an anarcho-syndicalist now, babe?

She particularly hated the pocket, which was one of the seed packets appliqued on the side. "Don't miss the pocket! Take a picture of that pocket!" I've known V almost forty years, and this is the closest I've come to hearing her actually hiss something.

Here's that pocket!:

Fun!

I thought one could accessorize the seed-packet dress with the Schiaparelli insect necklace below, but V was not buying it. "You don't make fun of farm women," was her final word on the matter.

I liked this necklace. The bugs are realistically molded, but painted in bright colors that make them, or at least some of them, look artificial. On their clear backing, it would look as if they were floating unsupported around your neck, to creepy and thrilling effect.

Still seething at Schiaparelli (a phrase I never, ever thought I would write), V was further irritated by the astrological symbols on the jacket below, though she was a bit mollified when a label said that the designer's use of planets and stars was a tribute to her beloved uncle, an astronomer (not astrologer), with whom she spent many childhood hours studying the nighttime skies. I also suggested to V that astrology was acceptable as a decorative motif, even for a math and science teacher like herself. I don't know if that helped.

We moved on from Schiaparelli. V liked the dress below very much.

Sometimes I became aware of how well the show was lit. The lights were generally dim, as they are for drawings or woodblock prints or other delicate works, in order to protect the fragile materials, but there were some effective spotlights.

The dress on the right below is called the "tart" dress. It looks quite respectable from this angle, and honestly my first, rather clueless, thought was "small pies? huh?" By process of elimination (no small pies were visible!) I realized that, yes, they meant the female kind of tart.

The name comes from the bold arrow-like inserts (red on the front, dark purple on the back) pointing up towards the breasts . . .

. . . and down towards the butt. (The dark purple below might show up a bit better if you can click to enlarge the photo.)

I forget the name of the woman who designed the tart dress, but she intended it as a feminist statement. I guess "being exploited for your sexuality" and "being 'empowered' by owning your sexuality" have been doing their little dance for quite some time. Nothing too surprising there. I thought the tart dress was stylish and bold, but honestly I'm not sure it's any more pointed than something like the Worth gown below, dated 1907 - 1910, which I photographed because it put me in mind of highly respectable females in the novels of Edith Wharton and Henry James. You can see that the neckline is quite low, and those flowing insert things (I think they were beaded) also underscore and draw attention to the breasts.

And you'd have to be a bold woman indeed to wear the dress below, inspired by the grandeur that was Greece and the glory that was Rome:

With a neckline like that, a red arrow would not really be necessary. You wouldn't even have fabric to put it on. (This is a different dress from the Grecian ones shown above.)

Though I was thinking a lot about different art movements while walking through the exhibit, I wasn't thinking that much about things like gender roles (that is most definitely not a complaint), because the slice of the world we're seeing here is so rarefied anyway, and these costumes (and that really is the right word) are so fanciful and often eccentrically individualistic. I'm not sure a woman could wear some of them twice – like the dress made out of huge poppies shown earlier; that sure struck me as a one-off.

But I guess the tiger dress below is meant as a sly comment on women as both predator and prey. I love tigers anyway, preferring them to lions, who always seem a bit worn out. We overheard one of the guards telling someone that the model in the backdrop photo, now an elderly woman, had come to see the show, and that she was incredibly charming and gracious. I felt oddly happy hearing that.

I'm really not sure what's going on with the big red flower on the dress below. Wouldn't it get in your way while you were reaching for a canapé? It seems sort of floppy and lopsided. I suggested to V that the dress would be improved if someone tore it off and she agreed. The big red flower was the only really egregiously puzzling thing we saw. Why did this seem like a good idea to the designer?

The dress below, however, struck me as cool (in every sense) and delightful; if it were blue and green instead of red I would consider it a perfect summer dress. It's almost like a superhero costume: if you're wearing this, you're marked out as someone with special powers, distinctive, not of this sweaty realm.

Since some consider the movies the great twentieth-century art form, it's not surprising that Hollywood and the fashion world played back and forth. The dress below, by the Fontana sisters of Italy, was worn by Ava Gardner in The Barefoot Contessa. In classic movie star style, she was apparently shorter than she looks on screen.

It seemed like something Columbina might wear in a really luxe Harlequinade, or an outfit Watteau would paint on a woman standing among the feathery leaves of shady melancholy trees.

The shoes and hats were all in vitrines, but only one of the dresses was: Charles James's Cloverleaf dress. There was a very interesting video in one of the rooms showing its elaborate construction. None of my photographs do it justice, as you really need an aerial view. The first one below gives you some idea of how it sweeps out in four distinct directions.

Here's a close-up of the lace. There were several versions of this dress, it seems, some of them in solid colors. This one was quite elaborate, with the lace and the rich fabric.

It was a triumph of engineering, and apparently James felt that way too. Seeing it and its mathematically produced elegance gave extra force to the Allegory of Geometry by Laurent de La Hyre (detail below) that we later saw in the baroque gallery.

Below is another James gown, the Siren. Some of the dresses had such a powerful presence that a mannequin would have lessened the aura. The frocks just stood there, absolute. I would do what this dress told me to do.

The gowns seemed to conjure up a whole vanished world of wit and elegance, a world that of course never existed: the women who wore these artworks were humans who would sweat, weep, defecate, struggle with or succumb to various appetites, who had blemishes, could get tired or sick, would grow old and die. These dresses were designed to float them above all that, at least temporarily, and above the rest of us. These fragile, easily damaged costumes seem monumental, like protective armor over fragile, easily damaged people.

When we left the exhibit it was actually raining outside, heavily enough so that we delayed leaving. Even a light rain is a remarkable thing to happen in California in early July, and though any precipitation is welcome during this drought, it seemed like another sign that larger unseen patterns were shifting around us.

After a brief walk to the bus stop, we hopped on the #1 California bus and headed to Chinatown, where we had a very enjoyable dinner, at a place we've gone to for years.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)